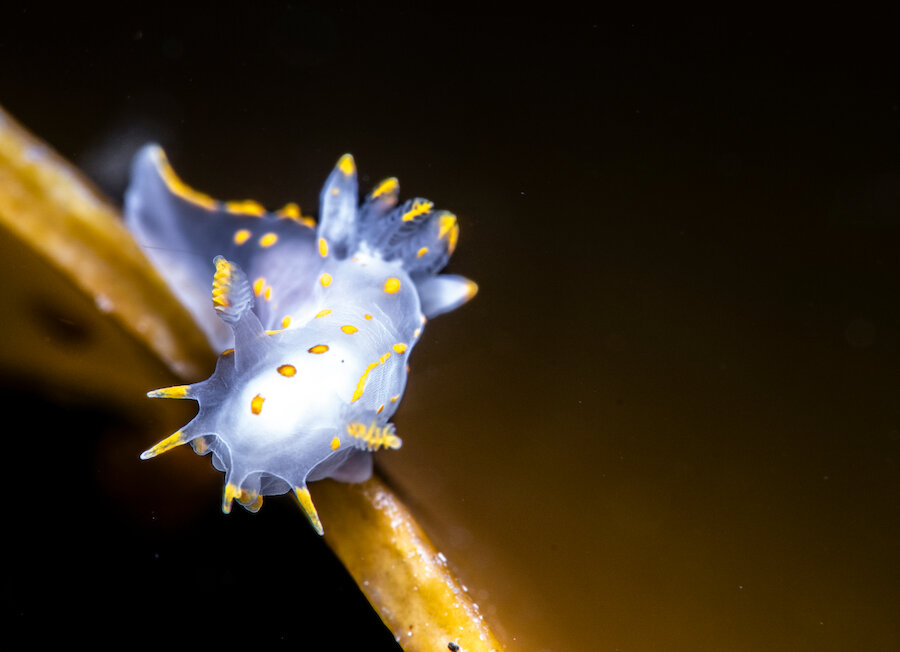

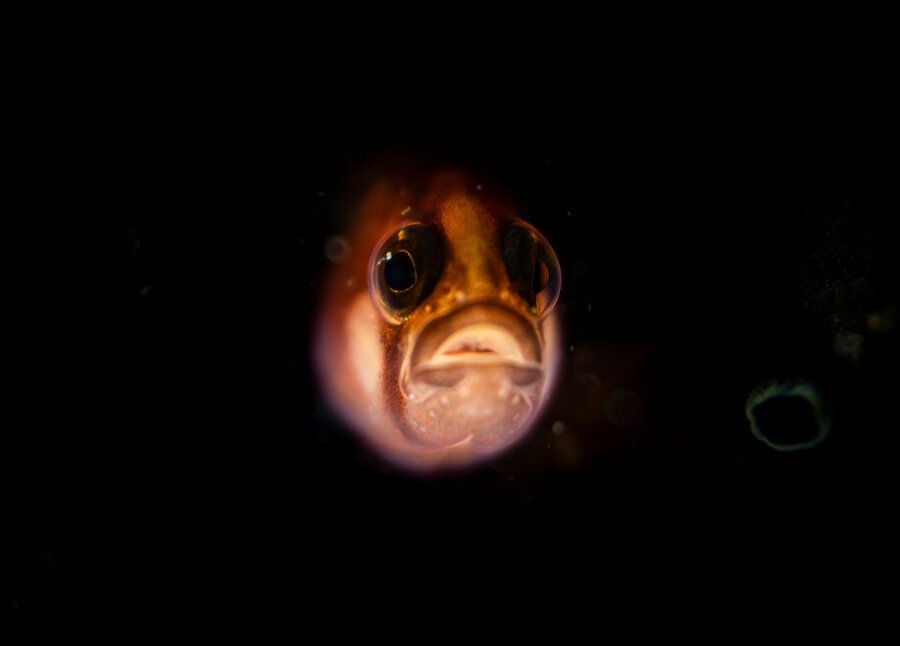

While many underwater photographers chase the big things, Shetlander Billy Arthur tends to focus on the tiny and undiscovered. His primary subjects are strange, almost alien creatures, with curious, sometimes descriptive names: nudibranchs, dead man’s fingers, Dahlia anemones, Devonshire cup coral. “They’re the things that a lot of divers don’t stop to really look at,” he says. “But to me they’re the most beautiful and fascinating.”

Like a lot of children in Shetland, Arthur grew up ‘platching the ebb’, the local term for exploring beaches and rock pools at low tide. “As a child, I was obsessed,” he says. “I’d constantly be looking under rocks for crabs or anything that moved, or studying guides to the shoreline.”

But it wasn’t until he went travelling that he learned to dive: doing his courses around Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, and later going on trips to big-ticket spots in Mexico, Thailand and Egypt’s Red Sea. His biggest revelation, though, came when he returned to Shetland in 2010, after studying in Edinburgh. “It was like discovering this new world, which is all around us but which we don’t often think about,” says Billy, who now lives at Dunrossness in the south of the Shetland Mainland. “I knew Shetland waters were rich, but I couldn’t believe the beauty and colour of some of the creatures down there.”

I knew Shetland waters were rich, but I couldn’t believe the beauty and colour of some of the creatures down there.

While working in the salmon industry for most of the past decade, he has developed his photography, using his mirrorless Sony a6500 in an aluminium housing, often with a 90mm macro lens and underwater strobes. And, as his photography has developed, so has his appreciation of underwater Shetland. “It’s now my favourite place to dive anywhere in the world,” he says. “In a lot of more famous dive locations, there are other boats and groups of people, all chasing the same things. Here, it’s often just me, my dive buddy and these cold, clear waters. It only gets more magical to me.”

Here, he explains some of his otherworldly shots.