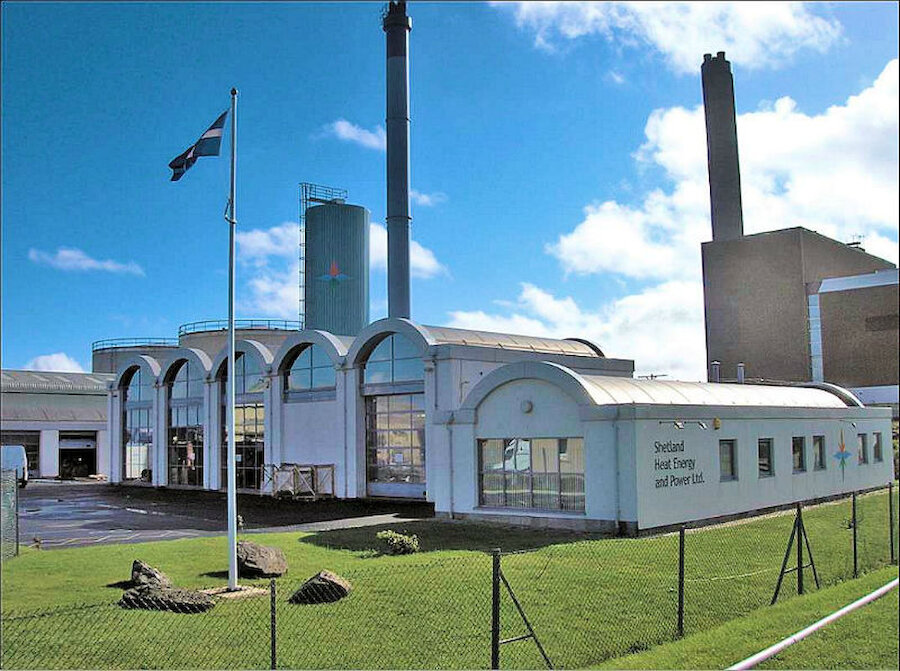

For more than twenty years, Shetland’s waste to energy system has used the islands’ combustible rubbish – supplemented by Orkney’s – to heat homes, businesses and public buildings in Lerwick.

At a time when all of us must try to reduce our carbon footprint, it significantly reduces the demand for heat generated from fossil fuel sources. It also reduces, dramatically, the need for waste to go to landfill, and there are other benefits.

The scheme was conceived in the early 1990s. The Shetland Islands Council had, for many years, operated an incinerator that simply burned rubbish, but it was faced with new environmental regulations with which the existing plant couldn’t comply.

The Shetland Charitable Trust was keen to make investments that benefitted the community and involved innovation. After studying examples of successful waste to energy schemes elsewhere, particularly in Denmark, both organisations gave the go-ahead for the main elements of the project in 1997, and the first customer was connected in November 1998.