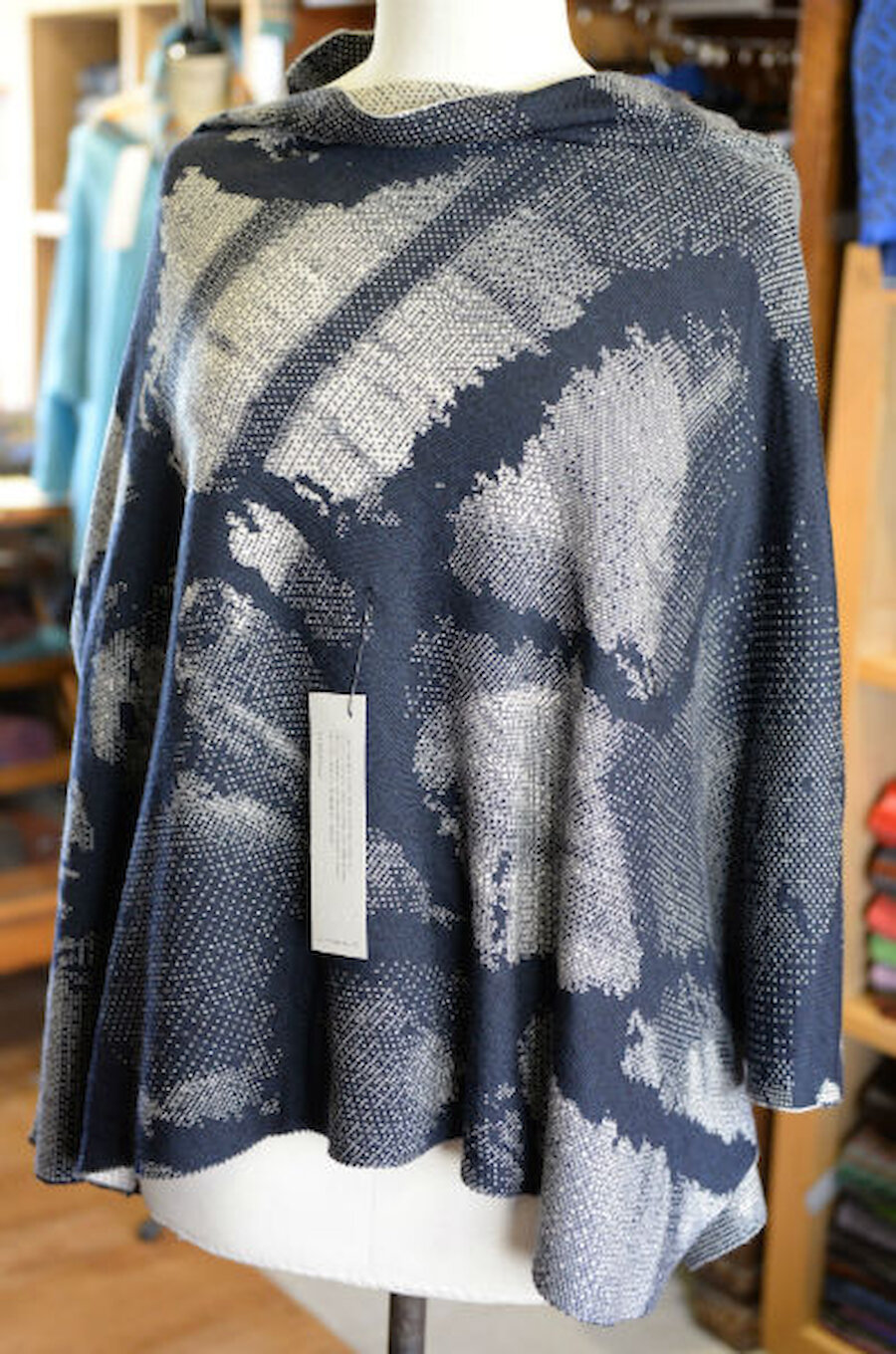

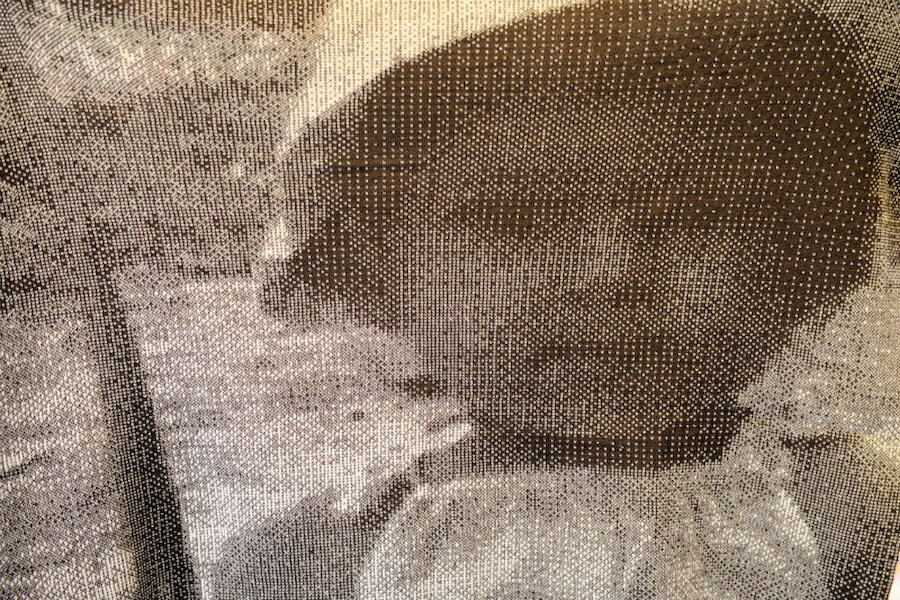

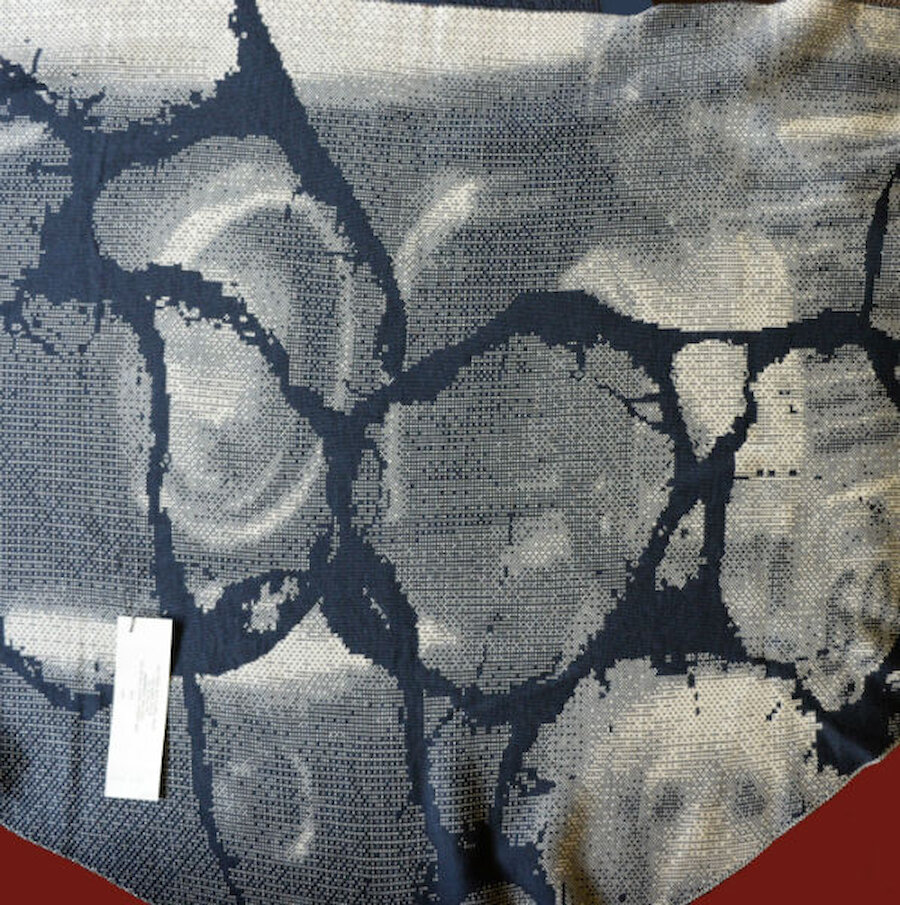

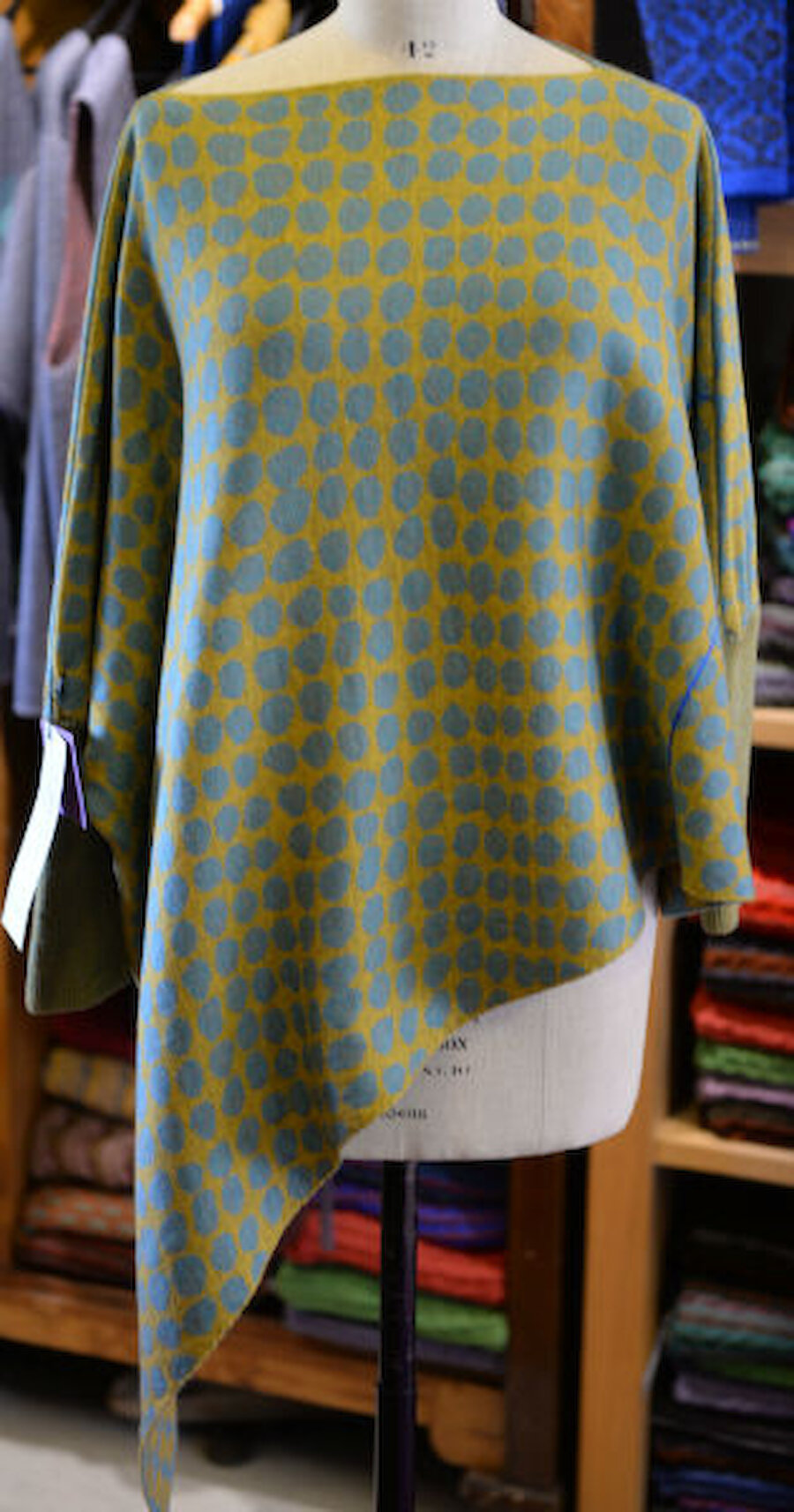

Over recent decades, Shetland has become known not only for the traditional Fair Isle and lace knitting on which the islands’ international reputation rests, but also for innovation in design and technique. One of those innovators is Niela Kalra, whose business, Nielanell, is now firmly established at the leading edge of Shetland textile design.

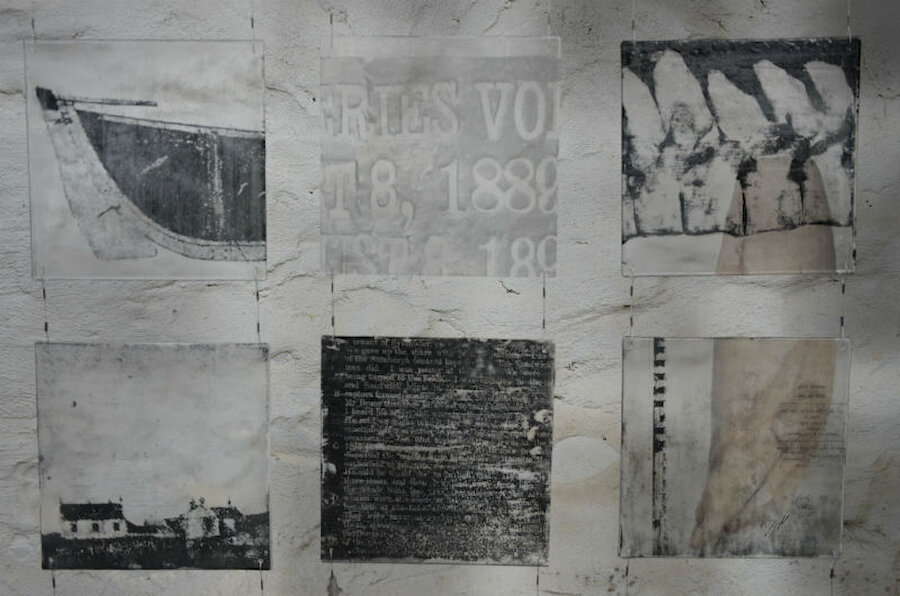

Born in Canada, she’s the daughter of an Indian professor and a Scottish nurse; her mother was also a weaver and opened The Westmount Weavery. “I would have been about five or six, my brother younger, and we used to spend a lot of time there as children, and as we grew up. I spent a lot of time holding hanks of yarn and helping mum warp the looms. I suppose we were just brought up in that kind of atmosphere.”

Both Niela’s grandmothers were also keen knitters . “I have a lovely photograph of my grandmother in India, sitting in a beautiful white sari, in a rocking chair, knitting. I still have some of the last things that she ever knitted. So, I was surrounded by woollen textiles. And, though I didn’t understand it at the time, my mother wasn’t just a maker, she thought quite out of the box. Although that was quite normal for me then, I realise, looking back, that it was this way that she expressed that in her textiles. That’s obviously been a deep influence.”