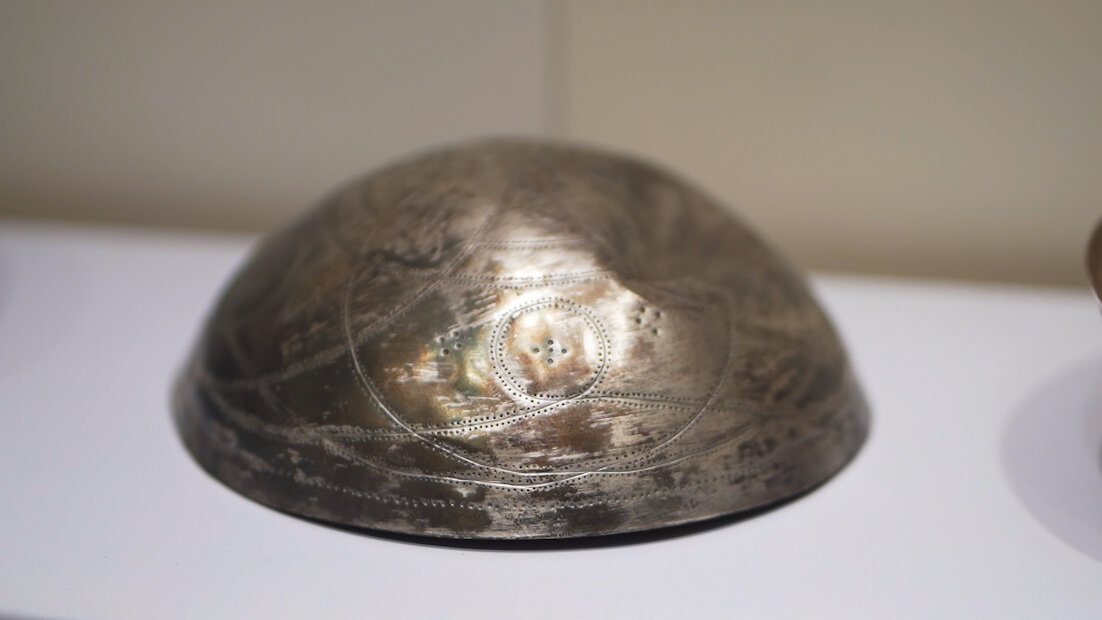

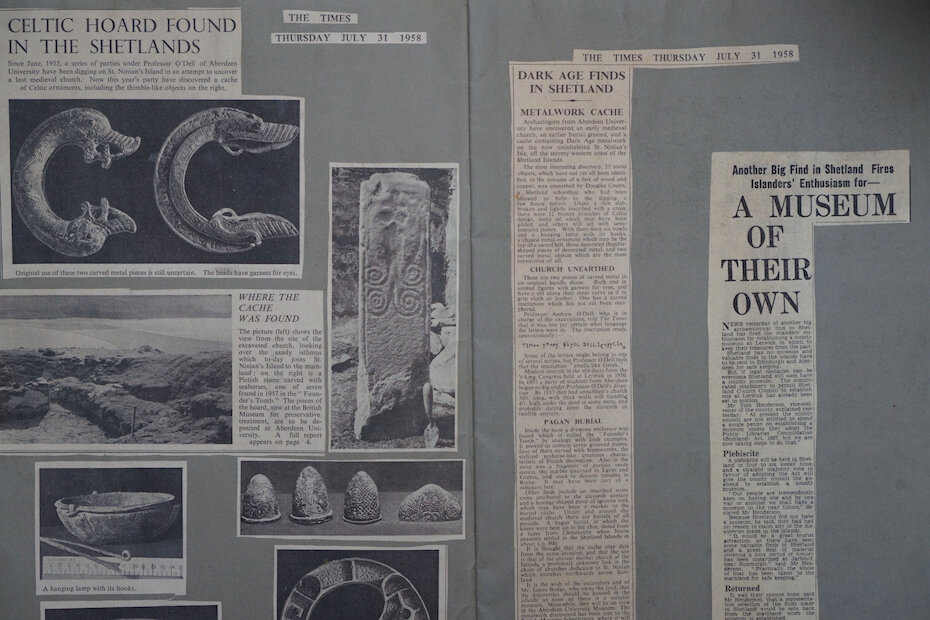

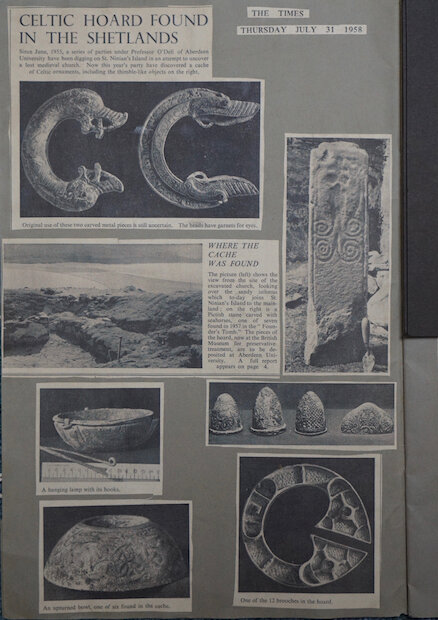

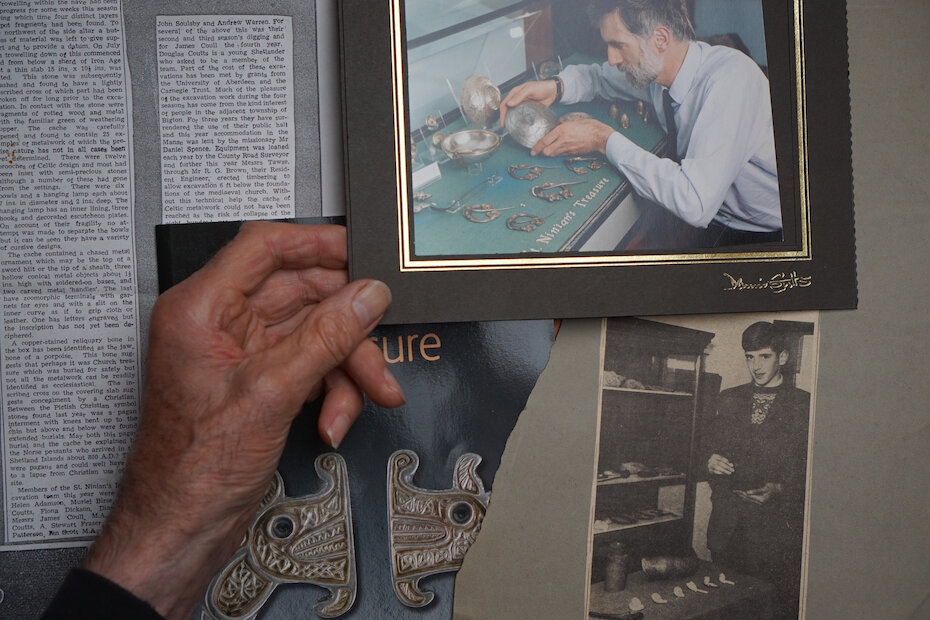

Much of this history had been lost, says Douglas, until Professor Andrew O’Dell from the University of Aberdeen was given permission to lead a team of archaeologists excavating the site during the 1950s.

The dig generated understandable interest in Shetland, including from the young Douglas Coutts.

“During the excavations there were signs of stonework underneath the walls, to suggest there had been a previous and earlier chapel, the more recent one being built on top of it…

“In 1955 when Prof O’Dell came here this was just a hill with no visible stonework to indicate that there was anything underneath.”

There were however clues kept alive in local lore. “There’s a map dated 1608, a Timothy Pont’s map of Shetland, that showed a cross roughly around this part of the island near the isthmus.

“In 1700 there was a writer, Brand, who was describing Shetland at the time. He came here and was able to see a ruined chapel in 1700. Another visitor came in 1861 and there was nothing to be seen, the chapel was completely covered and had disappeared under the ground.”

That is how it remained until the 1950s.