In his welcome to Shetland: Cooking on the Edge of the World, James Morton points out that co-authorship of food books may not be unusual but “fathers and sons working together on the same subject is…a little odd.” Perhaps, but in this case the proof of the pudding is in the reading.

James was a finalist in the third series of The Great British Bake Off, broadcast in late 2012. He’s subsequently written books about bread, baking in general and home brewing. He's made many appearances on television and at food festivals and all of that has had to be fitted around his training as a doctor.

His father is Tom Morton, “recovering” journalist, radio and television broadcaster and author, who has covered topics ranging from music to golf and whisky to motoring. For a year, he was the writer behind the “Oor Wullie” cartoon character in Scotland’s Sunday Post newspaper.

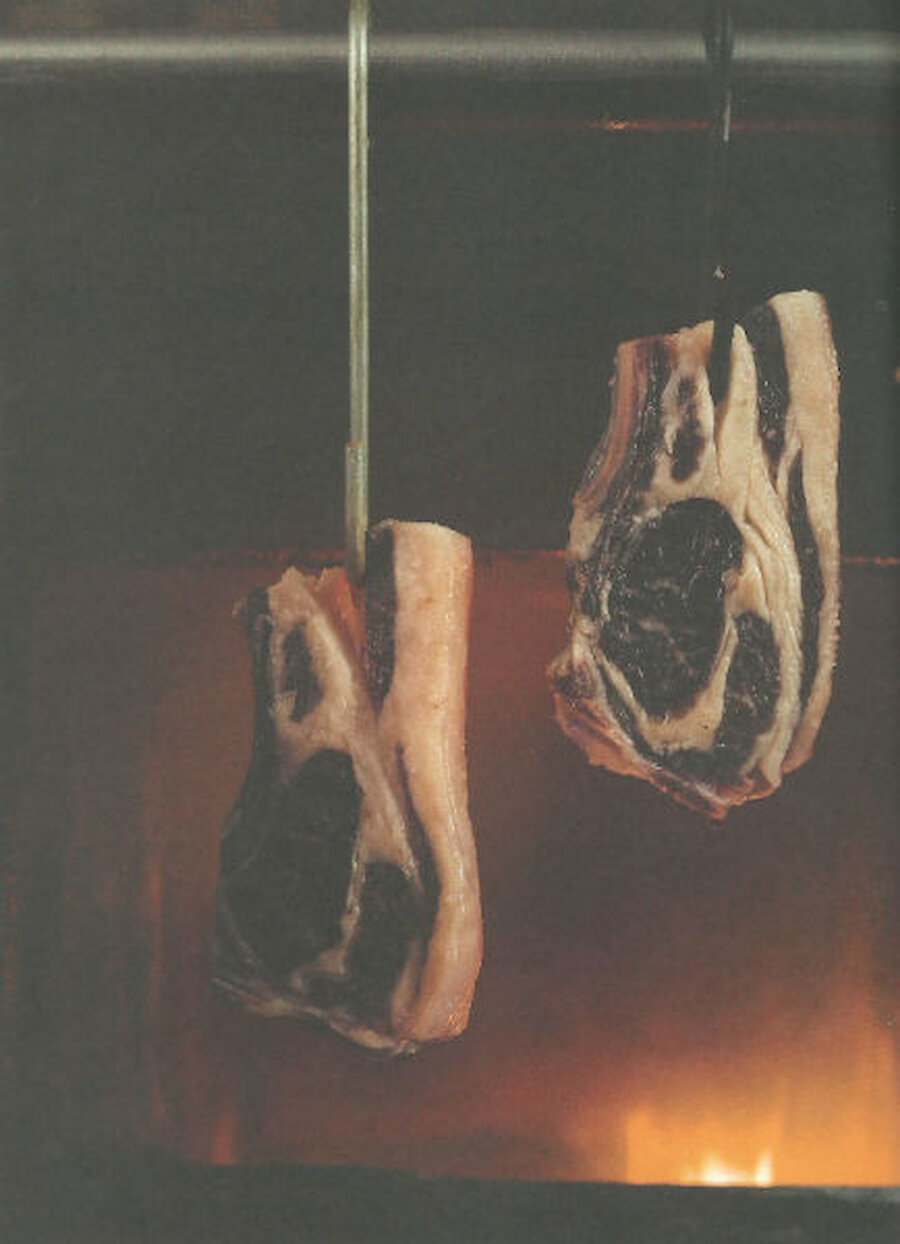

The family home is at Hillswick, in the beautiful district of Northmavine, the north-western corner of Shetland’s mainland. The many photographs by Andy Sewell that punctuate the text do full justice to the area’s wonderful coastal scenery and, of course, the food.

Neither Shetland nor Northmavine are ordinary places, and this is no ordinary cookbook. It opens with a brisk, fact-checking introduction to Shetland: no, it’s never ‘the Shetlands’; the nearest railway station is in Thurso, Scotland, not Bergen, Norway; and we’re in Shetland, not on Shetland.