It is now part of Steven’s regular work and he is increasingly aware that a key barrier to peatland restoration is public understanding. Before he began, Steven said he had very little knowledge of why it was such important work. He was “really surprised to learn there was more carbon held in peatland than in rain forests”.

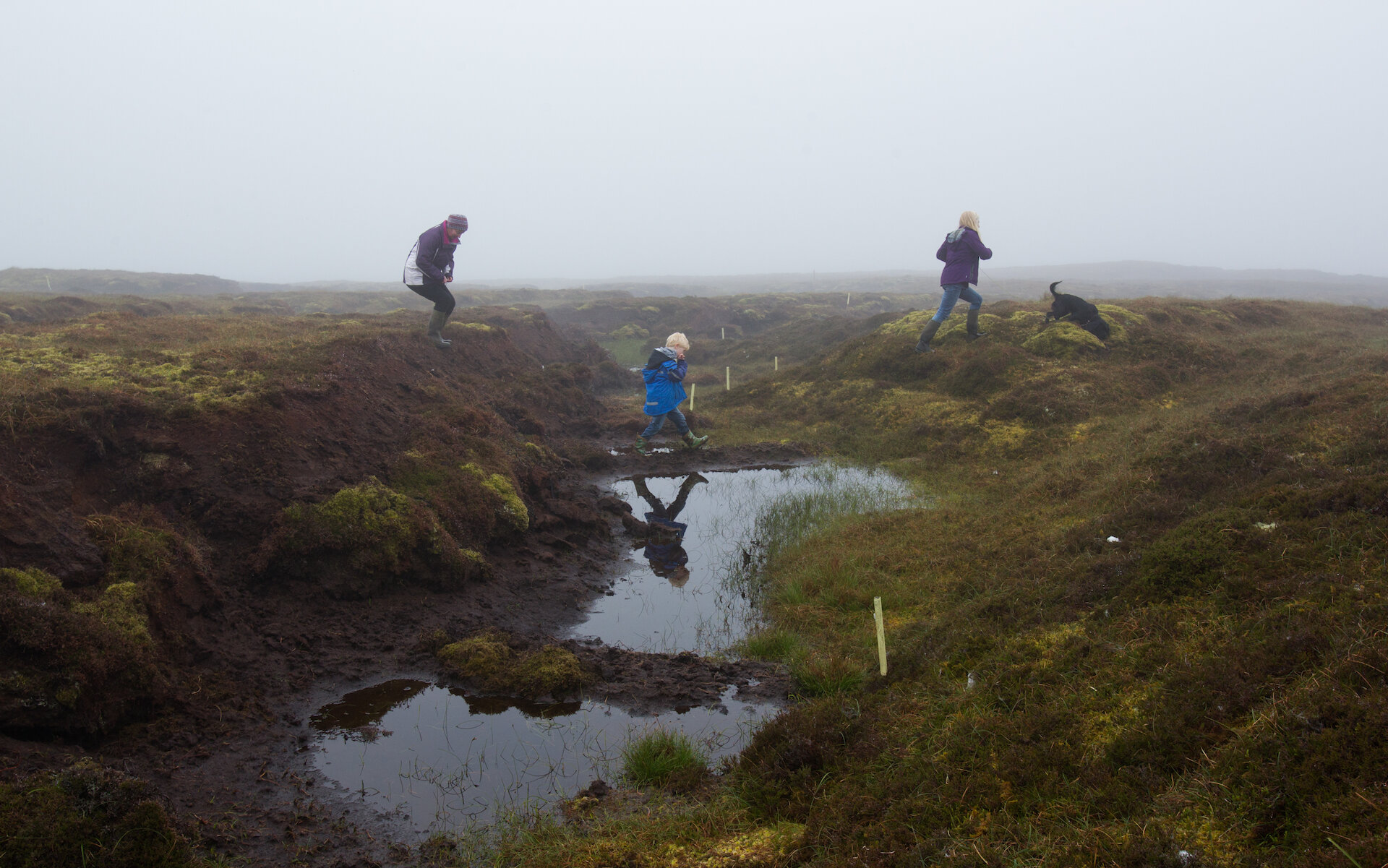

One of the biggest revelations during was the need to keep peatland wet to protect the ecosystem and the broader health of the peat bogs.

“And I didn't realise the importance of keeping everything so wet. To me, if you could drain it and dry it, that was probably going be better. So that was a new one.”

While Steven is a convert to a new way of thinking, Sue admits that changing perceptions is part of the challenge.

“I think so often folk get so used to thinking, you know, that's what the hills are meant to look like in Shetland. And it's quite a shift in perception to realise actually that's not what it's meant to look like. And when folks see what it could look like, they actually realise, ‘Wow, this is lovely'.

Healthy peatland, she says, has "pools and so on but they're going fill up with vegetation in time. It's going be heaving with invertebrates. The birds are going be in here feeding on all those invertebrates. It's going to be lovely.”

Visit the Shetland Amenity Trust website to find out how to get involved in supporting Shetland’s peatland restoration.

Find our all about Shetland's clean energy ambitions.