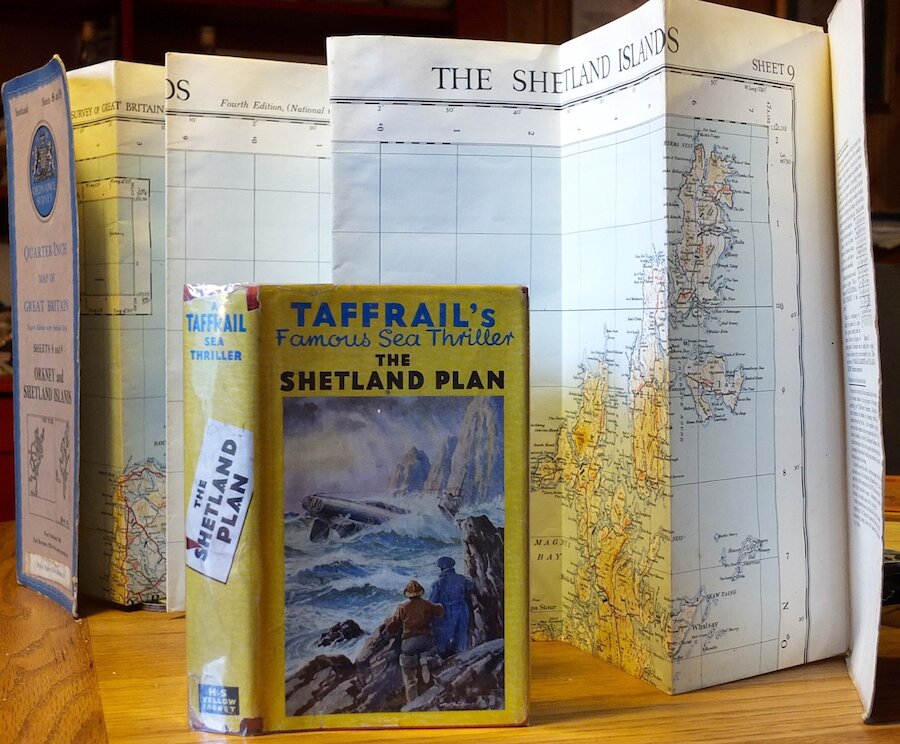

This description is early in the novel and prepares you for a glorious set of drives, walks and sea voyages on and around the isles. The family meet a mysterious German refugee called Mr Boomer, the landowner Sir Richard Carmel, his wife, Lady Carmel (who also has a repulsive dog) and their daughter Alice. The Carmels have a 50-foot motor launch called Olna which is crucial to the action. This involves the sighting of a submarine, the discovery of an arms cache at the abandoned whaling station also called Olna (between Voe and Brae), and the pursuit of a gang of German spies who murder one of the main characters. An aircraft carrier, several destroyers and a survey ship are involved. While the book begins in quite a jokey, Swallows and Amazons sort of way, it ends with….well. Let’s just say it gets serious. There is, as you might expect, frequent rampant sexism and gender stereotyping, not to mention some rough attempts at Shetland dialect and misspelled place names. But it has tremendous pace and, as I say, a delight in and sense of place.

I spent a day or two tracing the locations mentioned or hinted at in the book and travelling to them by car. I would love, in summer, to follow the Olna’s marine voyages, especially the high speed trip to Scalloway and back to Bridge of Walls and then Gonfirth and Voe. I was especially interested in the family’s base while in Shetland, “The Bridge of Walls Hotel”. Thanks to Mariane Tarrant and Rose Young, longstanding residents of the West Side, I discovered that the long straggle of (now restored and converted into a single, private residence) old houses just opposite the bus stop at Brig o’Waas had indeed been a former shop and fishing hotel, at a time when angling in Shetland and Orkney was a major tourism attraction. I’d never even given the place a second glance, but sure enough, the description in The Shetland Plan still matches up:

The hotel obviously hadn’t been built as such. It looked more like three cottages knocked into one - a long, two storied house of grey stone, with a row of dormer windows in the slate roof giving light and air to the bedrooms on the second floor. It stood on a terrace overlooking a narrow patch of walled garden, beyond which was Browland Voe.

I had more trouble with Sir Richard and Lady Carmel’s house “near a little village called Gonfirth” reached in the Carmels’ chauffeur-driven Mostyn car by driving

…to the little village of Aith and, twisting and turning, along part of the east shore of Aith Voe, through East Burrafirth, up hill and down again over a tract of wild, undulating moorland, and so to Gonfirth. From here, turning left, the chauffeur came down to low gear to negotiate what was little more than a rough cart track winding through the heather, with view of sea and islands in the distance.

I initially thought Dorling was describing East House, Grobsness, though South Voxter and the abandoned Lea of Gonfirth (home of the legendary cake cupboard) were also possibilities. However, the fact that “Andy recognised the old anchorage of the Tenth Cruiser Squadron...the irreverent used to call them The Muckle Flugga Hussars” also made me think of the Old Haa at Grobsness. In the end, though, I plumped for the most obvious choice: Vementry House, which Dorling would certainly have visited, and perhaps wanted to disguise from just my variety of tourist. Approaching from the sea or the road, Vementry does sort of appear like a row of three or four squat, single-storeyed cottages apparently knocked into one, with some modern looking outbuildings at the far end. They lay within 50 yards of the rock shore of Gonfirth, with a stretch of sloping lawn.

But there is, in Vementry’s case, that inconvenient Georgian manse-like structure at one end. Maybe it’s South Voxter, Cole or as I say, perhaps Dorling was being a little deceptive, for the sake of his hosts’ privacy.