Visitors to these three island groups are often surprised by the contrasts between them. They look different: mountains and vast beaches in Harris; the rich pastures of mostly low-lying Orkney; and the rugged scenery and spectacular cliffs of much of Shetland. In Shetland and the Western Isles, agriculture - and the landscape it creates - are rooted in crofting, whereas farms are the norm in Orkney.

A project called Between Islands, which was developed by An Lanntair, the Western Isles’ arts centre, aims to explore the arts and heritage of that island group alongside those of Orkney and Shetland. With funding from a range of sources, there’s now a wealth of material online.

Cultural comparisons reveal differences, too. The culture of the Western Isles is strongly Celtic , with Gaelic widely used. In Orkney and Shetland, there was once a Pictish culture, but it was overwhelmed by Norse settlement; neither island group was ever part of the Gaelic tradition. Instead, they have their own dialects blending Scots, old Norse and English.

However, there are common elements, too. All three groups have a similar maritime climate, windy but relatively mild thanks to the North Atlantic Drift, or Gulf Stream. The long spell of cold and frosty weather which affected them all in early 2021 is highly unusual, thanks to the sea’s influence.

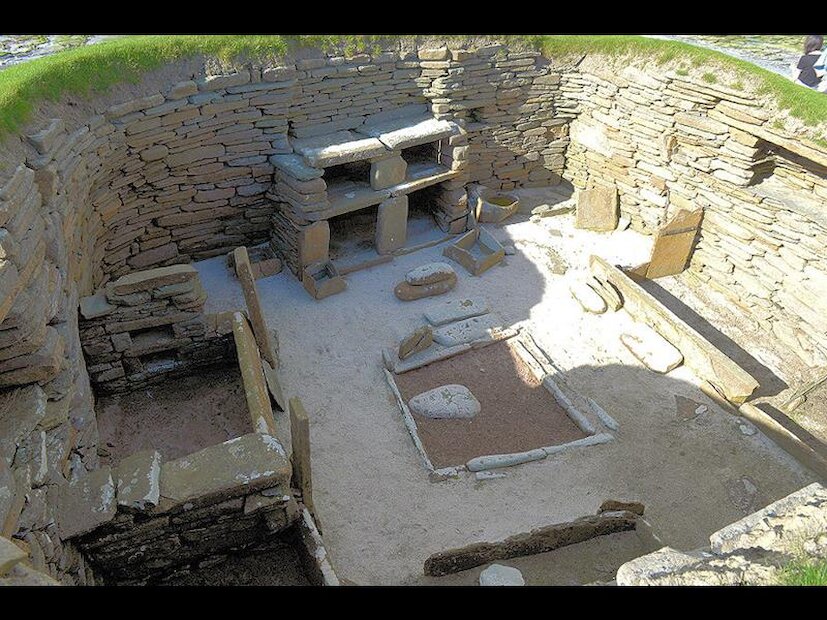

All are rich in archaeological remains, with Neolithic, Bronze Age, Iron Age and Norse period monuments. Settlements feature standing stones at Callanish, Lewis; the well-known domestic interiors at Skara Brae in Orkney; and wheelhouses at Jarlshof in Shetland. In all the islands, there are numerous brochs, though the one on Mousa, Shetland is the only one that’s virtually complete.

Another common factor is the presence of truly vibrant and diverse artistic, craft and musical communities; and it’s on these that a project called Between Islands focuses.

Music, in fact, was the catalyst. Creative Scotland sponsored a collaboration between songwriters active in all three island groups with the aim of encouraging them to write together on the theme of islands. The three selected were Willie Campbell from Lewis, Kris Drever from Orkney and Arthur Nicolson from Shetland. As project co-ordinator Alex MacDonald explains:

“…they were artists broadly known for different styles of music, although none of them can be pigeonholed. Willie was best known as a member of indie band Astrid, Arthur had just won a Danny Kyle award at Celtic Connections, and Kris was much in demand in the world of folk and roots. In addition, and although I knew them all, they hadn’t worked together before. Nor, I remembered as our plane landed in Sumburgh, had Willie even met either of the people he was just about to work with. It had been viewed as a risky set of circumstances by some, and at that moment I wondered if they were right.

However, within a day there was a song in the bag”.

More songs followed, and by the middle of 2015 they had been performed in all three islands. The three songwriters appeared at the Hebridean Celtic Festival in 2019, by which time Between Islands had expanded to embrace museum exhibitions, lectures, films and more, including an excellent YouTube channel that’s well worth exploring. In the meantime, other projects had been undertaken under the same banner; one brought together fiddle players and another took as its theme a commemoration of the First World War.

The project reminded audiences of the very tangible links that have existed between the islands. For example, a Gaelic song – in the (unaccompanied) mouth music so often heard in the Western Isles – recalled the herring gutters who travelled from there to work in Orkney and Shetland. The school choir in Stornoway performed in Shetland dialect and Orkney children sang in Gaelic. You can find a half-hour compilation of songs from the project here

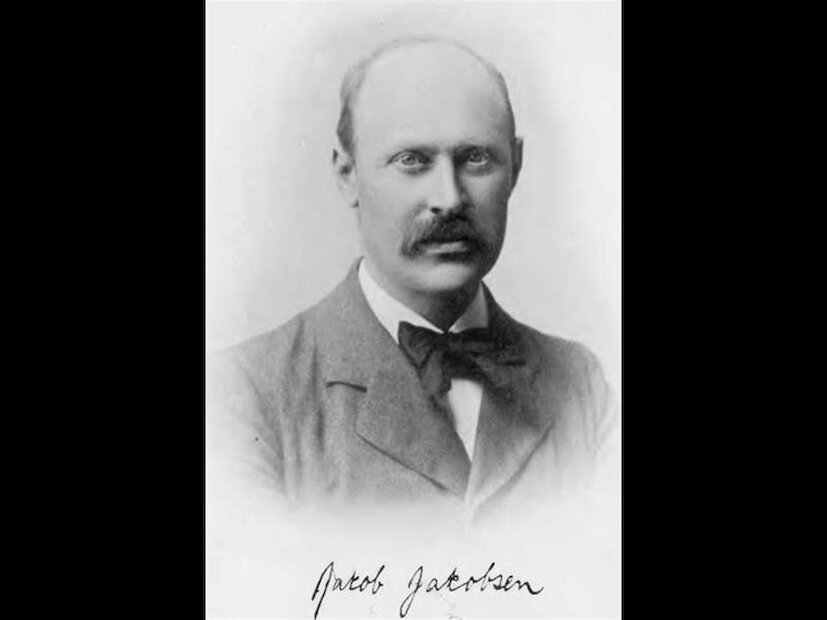

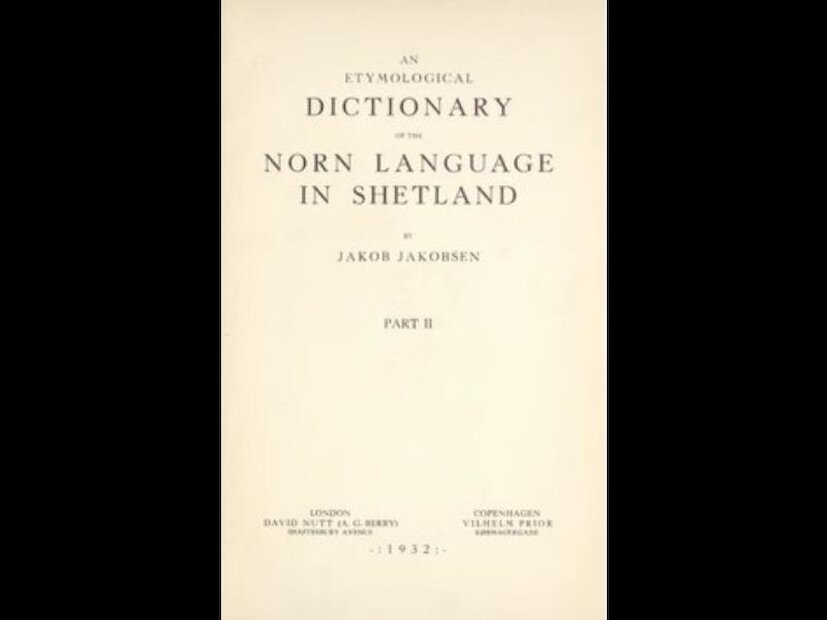

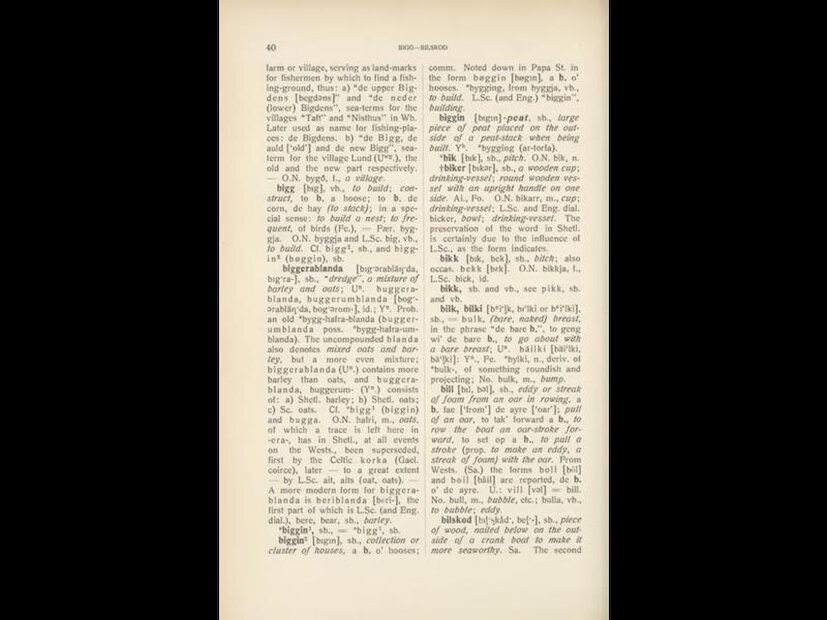

Between Islands developed other cultural strands. One of the many videos created by the project is about Shetland’s dialect, with extracts from Shetland writing and explanations from dialect speakers. The dialect was comprehensively recorded between 1893 and 1895 by a Faroese scholar, Jakob Jakobsen, and his dictionary was published in its two-volume English version in 1928 and 1932.

The dialect has undergone a revival in recent decades. That’s in large part thanks to initiatives such as Shetland Forwirds, and it has also helped that the BBC’s local station has supported its use. Mary Blance, working at the newly-founded Radio Shetland in 1978, was the first to use dialect on air, but explains that there were complaints – some people just didn’t want to hear it and thought its use should be confined to the home. As Mary explains in the video, “English was the language of power, and they did try, many many times, to eradicate the dialect, simply by getting bairns to speak English in school; and that was for centuries. But we still have a Shetland dialect.” Words are in daily use for weather, crofting, food, birds and much else; and - as Mary recalls with amusement - “what we think about folk”.

It was no wonder that Jakobsen took such a close interest in Shetland dialect, because it takes in so many Old Norse words, and Old Norse is the foundation of modern Faroese and Icelandic. Shetland bird-watchers will refer to an oystercatcher as a shalder; their Faroese counterparts call it a tjaldur, and the words sound almost exactly the same.

Orkney, too, has its dialect, and there are both similarities and differences between it and the Shetland one. For example, Orcadians will refer to something small as peedie, whereas in Shetland the word is peerie. In the Western Isles, Gaelic is very much alive, and it’s actively promoted through Gaelic-language broadcasting, including the television channel, BBC Alba and BBC Radio nan Gàidheal

Words are in daily use for weather, crofting, food, birds and much else

Another project rooted in Shetland but emphasising the links with Orkney and the Western Isles has led to the creation of an online exhibition, Fair Game, which focuses on three activities – hunting seabirds and their eggs; whaling; and cutting peat. There are short videos on the YouTube channel to accompany these themes.

Though all have been challenged on ethical or environmental grounds in more recent times, they were once part of life in the islands. Only peat cutting and – to a very limited extent, in Lewis – bird hunting have survived into the 21st century. The exhibition, curated by the Shetland Museum and Archives, brings together photographs and related quotations.

Exhibitions have also been mounted online from Orkney and the Western Isles.

The Orkney exhibition, Culture and Life in Atlantic Scotland, focuses on the arts, crafts and literature of all three island groups. It explores the visual arts through examples of painting drawn from their respective museums and galleries. The section on crafts explores the strong textile traditions represented by Harris tweed and Fair Isle knitwear, but it also looks at other craft forms, for example the straw-backed chairs from Fair Isle and Orkney, and the skills evident in the maing of other domestic items such as churns in Shetland. There are home-made hide rivlins (slippers) from Orkney, too.

On a larger scale, the page pays tribute to building crafts and in particular the magnificent St Magnus Cathedral in Kirkwall.

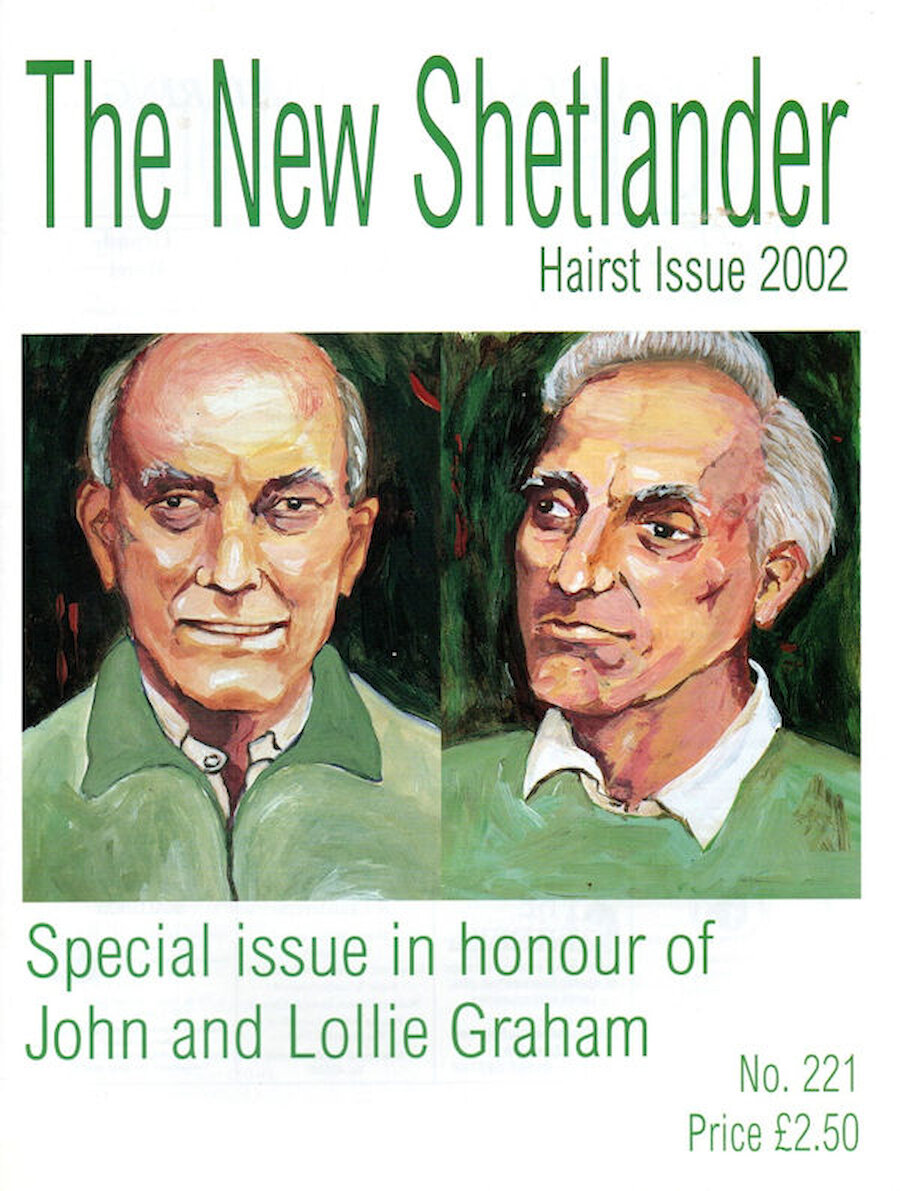

Literature, too, is part of life in the islands. Between Islands celebrates the The New Shetlander, the oldest literary magazine published in Scotland, which has enabled writers from Shetland and beyond to bring their work to the public. As well as Shetland writers such as poet Jack Peterson, contributors have included George Mackay Brown from Orkney and the Scottish poet, Hugh MacDiarmid, who spent some years writing in Whalsay. In the Western Isles, the work of Iain Crichton Smith and Sorley Maclean is recognised as part of the Scottish literary renaissance.

The online exhibition from the Western Isles is entitled Tales of the Unexpected and it’s a reminder, especially to those unfamiliar with the three island groups, of just how surprising they can be. The exhibits explore pioneering places, industrious islands, living traditions, extraordinary people and islands of design.

Pioneering places shines a light on the roles of the Western Isles and Shetland in past, present and future rocket technology, including the rocket range in South Uist and the proposed satellite launch centre in Unst. There is an account of the wartime role of the islands and their people, including that of Scapa Flow in Orkney, and we also learn about copper mining in Shetland, precious stones from the Western Isles and the more recent role of oil exploration in the islands’ economies.

Technology is celebrated in the Industrious islands pages, ranging from pharmaceuticals in Lewis to the surprising, if fairly brief, flourishing of 19th century straw hat manufacture in Orkney and Shetland. Living traditions focuses on weddings but also takes in the trows (mischievous fairies) of Orkney and Shetland and the guising traditions of Shetland and the Western Isles, including straw-clad skeklers in the former and sheepskin-bearing guisers in the Western Isles. There’s also a page on Up Helly Aa. The pages on extraordinary people embrace the Pictish and Norse cultures and islands of design looks at the place of island textiles in fashion and at the differing furniture traditions in the three groups.

With dozens of online exhibits to explore, the Between Islands project offers a very engaging and, yes, often surprising perspective on island life. There are rich and varied cultures to explore, historic and contemporary, and the project also throws light on the place that the islands occupy today and the way in which they contribute to present-day music, art, design, science and technology. Pulling all of this together and making the account so coherent is a remarkable achievement. Credit goes to those at An Lanntair who inspired it and all those across the Western Isles, Orkney and Shetland who worked so hard to bring it to us in challenging times. We may hope that, once travel becomes possible, the links between the islands will flourish again physically as well as virtually.