It’s no surprise, then, that islanders would want to work internationally, in this case to combat the tide of plastic and other detritus that has become such an unwelcome component of the world’s marine environment. For one thing, Shetland’s largest traditional industry is fishing, and fishing depends for its prosperity on clean seas.

In recent decades, Shetland has been active internationally in two organisations combatting a contemporary threat, marine pollution. That sort of collaboration is nothing new, because, for centuries, the islands have benefitted from international links and networks. The islands were an essential staging post for Viking explorers and, in the 16th and 17th centuries, German traders involved in the Hanseatic League set up bases in several parts of Shetland.

Today’s marine pollution presents several threats. Clearly, nobody would wish to see the marine environment and the food chain degraded by pollution. Wildlife suffers: seabirds, seals, whales and other sea creatures ingest plastic and die. We don't want to find plastic and other kinds of debris littering our beaches. And fishing crews lose valuable time, and may even risk their lives, when marine litter finds its way into their nets, or fouls the boat’s propeller.

In the 1980s, the issue of pollution rose up the political agenda, partly because of several major incidents involving oil tankers. These included the Amoco Cadiz off Brittany in 1978 and the Exxon Valdez in Alaska in 1989, both of which were catastrophic for local fishing communities; and there were many others. Shetland had its own disaster in 1993, with the grounding of the Braer, but – thanks to the time of year and the weather – the effects were much less severe than they might have been.

But oil wasn’t the only concern; plastic pollution was increasing and there were worries, too, about toxic chemicals and radioactive waste. The communities that were most affected by these incidents were coastal ones and it was from them that the calls for action were increasingly heard.

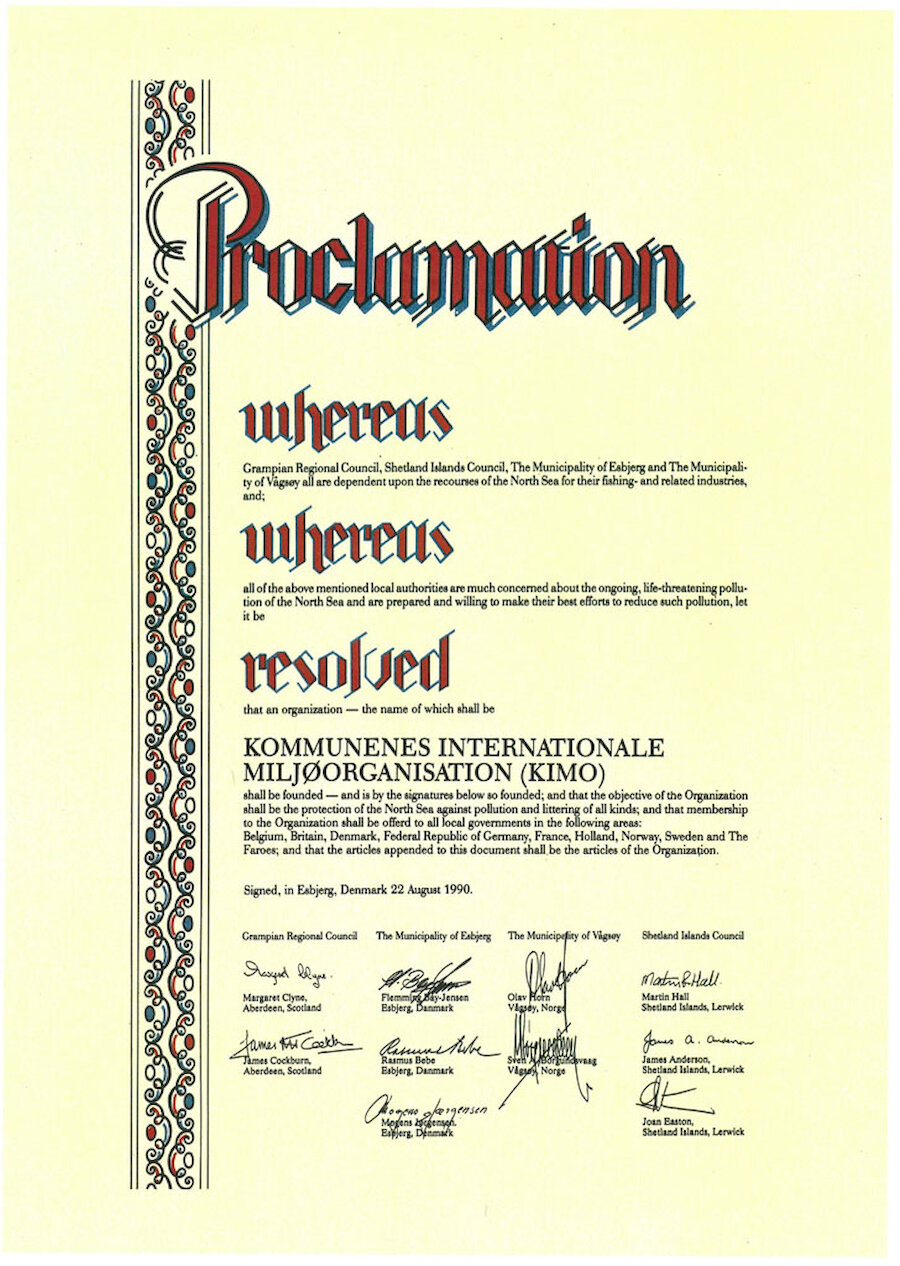

Shetland was among the first local authorities to throw its weight behind anti-pollution measures. On 22 August 1990, at a meeting in Esbjerg, Denmark, Shetland Islands Council became one of the four founding members of a new international organisation which enables local authorities to work together in order to tackle these problems. KIMO is an acronym for the organisation’s Danish name, Kommunenes Internationale Miljøorganisation. The Municipality of Esbjerg was another founding member and the other two were Grampian Regional Council and, in Norway, the Municipality of Vågsøy. Today, KIMO has five national networks; one involves the Netherlands and Belgium and the others are Denmark, Norway, Sweden and the United Kingdom. There are also members in the Faroe Islands, Germany, Ireland and Lithuania. Between them, the many local authorities involved represent more than five million citizens.

The secretariat has been hosted, from the beginning, in Shetland; and, as Councillor Morag Lyall explained to BBC Radio Shetland, that commitment continues:

“The seas around Shetland are one of our prime assets and they need to be kept as clean and pristine as they can, so a project like this is really valuable. The Council will do what it can to support it through our involvement in KIMO.”

KIMO has been active in a number of ways. It represents its members at a range of international forums including the International Maritime Organisation, the European Commission and OSPAR, a north-east Atlantic collaboration between the EU and 15 governments. KIMO develops and implements projects and acts as an exchange for information, for example about new legislation. The sharing of experience is also a priority.

Fishing for Litter is one of the projects which has grown out of, and is supported by, the KIMO network, OSPAR and others. It’s been hugely successful in encouraging fishermen to take ashore litter and abandoned, lost or discarded fishing gear that they find during their normal fishing activities. It began in the Netherlands as a pilot project and continues to operate there, in the Faroe Islands and the UK, under the KIMO banner. However, with OSPAR’s support, it has expanded to cover 10 countries, and similar schemes are under way in, among other places, Belgium, Germany, Greece, Ireland and Italy. A website that brings all these projects together was launched in 2021 and it has symbolised and encouraged cooperation between international partners that now stretches back over more than 15 years.

Jan Joris Midavaine, who coordinates the Dutch Fishing for Litter project for KIMO Netherlands and Belgium said:

“Sharing best practice and learning from colleagues about how they have faced challenges in their projects is really useful. We are sure that this new cooperation will bring benefits to everyone involved.”

However, the international commitment to Fishing for Litter extends beyond the members of the scheme. A new directive from the European Union relating to port reception facilities will make specific provision for waste arising from the programme. It’s hoped that this will prompt still more ports to take part.

The pollution problem may be complex but Fishing for Litter is a simple concept. Projects provide large, hard-wearing bags to boats, which volunteer to participate in the scheme. Fishermen continue to work as usual, but they bring any waste caught alongside the catch back to port. The project covers the costs of collection and disposal and demonstrates the fishing industry’s commitment to a healthy environment.

One growing problem is the loss of containers overboard from cargo vessels, creating another wave of debris in the oceans and on our beaches. Another issue is that of discarded fishing nets, specifically those used by foreign vessels in a technique known as gill-netting. Shetland fishermen and anti-pollution campaigners have convinced Shetland Islands Council to approach the Scottish Government about that.

However, shipping isn’t the biggest source of litter; KIMO reckons that around 80% of marine rubbish originates from land.

In Shetland, approximately 58 tonnes of litter has been brought ashore since more than 30 local boats from the ports of Lerwick, Scalloway and Cullivoe first became involved. Since 2005, across 20 Scottish ports, the total collected by almost 300 boats stands at 2,000 tonnes, an achievement marked when representatives of KIMO and local participants met in Lerwick, pictured above.

As Daniel Lawson, of the Shetland Fishermen’s Association, told BBC Radio Shetland:

“All our vessels are signed up, through the Association, to the Fishing for Litter scheme. It’s a really good project; all this bruck that’s at sea, they find it in their trawls and then bring it ashore. It hopefully goes to show that the fleet here is environmentally conscious…and want to clean up the sea as and when they can.”

Meanwhile, almost everyone is keen to improve the processing of waste returned to port, so that more of it can be upcycled or recycled, rather than being sent to landfill or incineration. One example of recycling involves the making of plant pots from recovered rope, net or fish boxes.

There’s no simple solution to marine pollution, because it takes many different forms and originates from an almost infinite range of sources. It comes at many different scales, too, from those micro-fibres shed by synthetic clothing fabrics to all manner of larger objects such as oil drums and nets.

We can all do something to reduce its impact, either by disposing of waste carefully or – if we’re visiting the coast – playing a small part in safely collecting and removing what we find. In Shetland, for decades, the annual Voar Redd Up, organised by the Shetland Amenity Trust, has been drawing thousands of volunteers – often, almost a fifth of the population – to spring-clean the islands, with much of that effort focused on the beaches.

You can follow Fishing for Litter on the project website and on Facebook and Twitter.