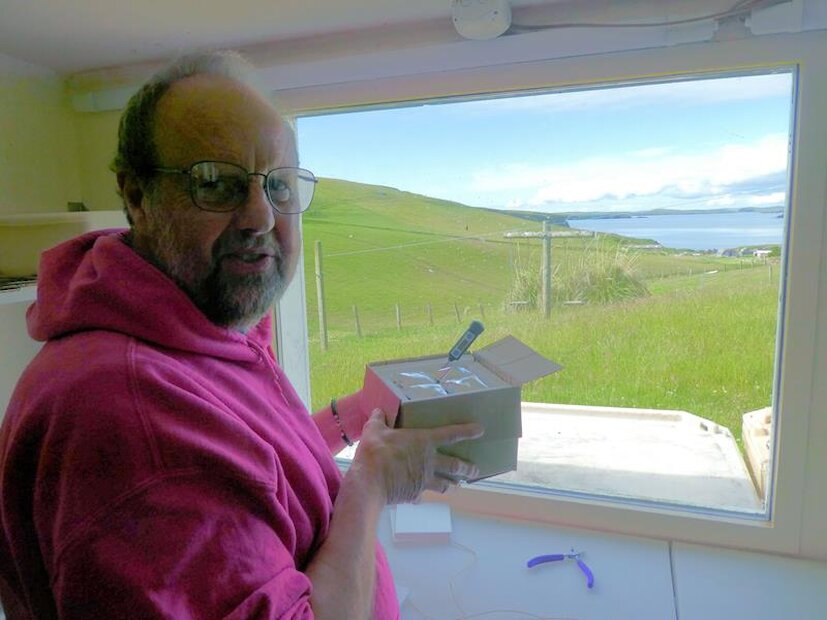

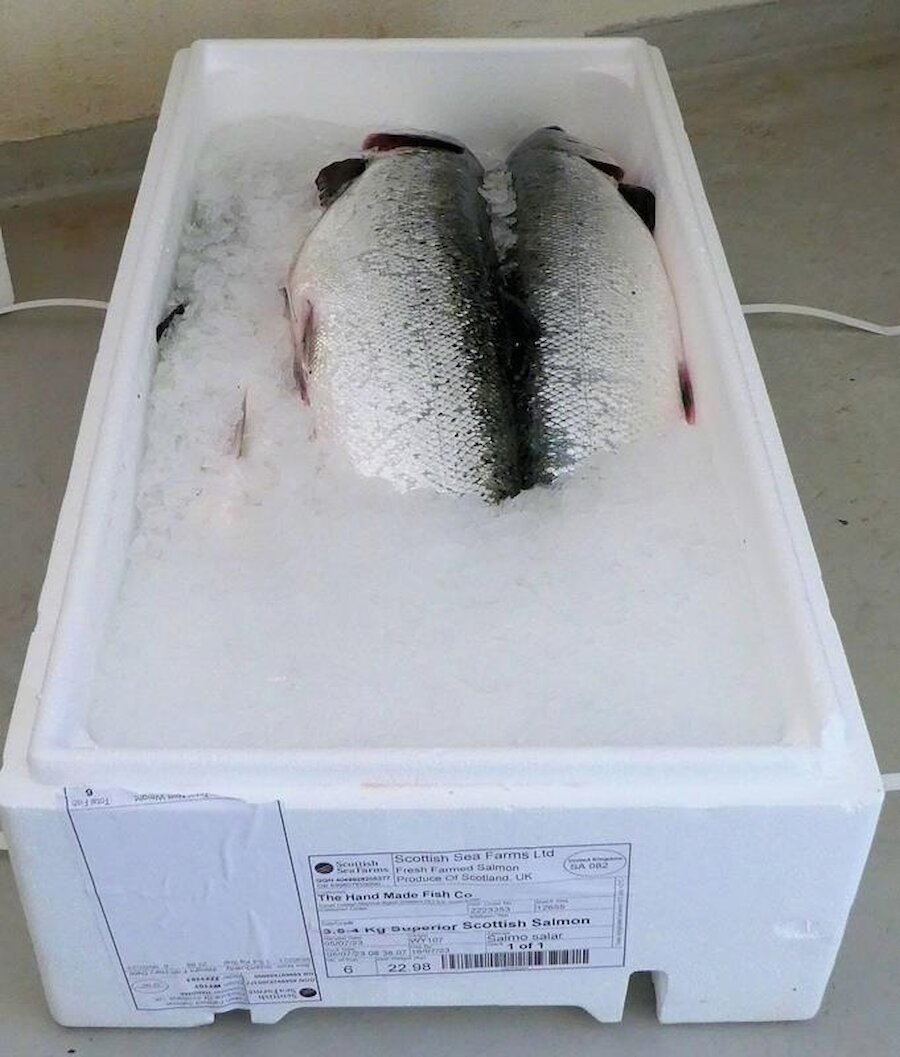

Dave is, quite rightly, obsessed with quality and he’s generally very impressed by the fish that he’s able to buy in Shetland. Nevertheless, despite their overall excellence, there are subtle variations, mostly because the strength of tides varies between the sites at which the fish are reared. A salmon reared in an area with particularly strong tides, like Balta Sound in the northernmost island of Unst, will be ‘a completely different fish’ from one reared where tides flow more slowly. One of Dave’s tasks is to balance these natural variations so that the product is as consistent as possible.

The skill, experience and attention to detail that goes into this is profound. “You have to be able to look at the outside of the fish and have some idea of how it’s life has been”. Then, “when you’re filleting it, what you’re looking for is reassurance that what you saw from the outside was actually right. And you’ve got to know, from looking at the outside, if you’ve aged it enough. Once you’ve filleted it, you can’t age it any more.”

Not all kinds of food are suitable for smoking, Dave feels, indeed he thinks that most foods taste better in their natural, unadulterated state than they do when smoked. He reckons that for something to taste good when smoked, there has to be some fat content – though an exception, he says, is smoked haddock. Duck works much better than chicken, as he discovered when asked to design a smoker for chicken for one of the kitchens for ‘Deliverance’ in London. Years ago, he smoked squid, and it’s “the best bacon you’ve ever eaten in your life! Absolutely stunning!”

Mussels can work, but other kinds of shellfish don’t. In all of this, he adds, it’s important to remember that 80% of taste is actually smell.

The effect of smoking depends on the temperature at which the wood is burning in the smoker. The oak sawdust ignites at about 290°C and he tries to keep the burning temperature no higher than about 310°C. Using his own fine-grained sawdust made from an un-seasoned oak log that is slightly damp helps achieve that. The temperature of the smoke when it reaches the salmon needs to be as low as possible, and certainly no more than 30°C; “the colder the better”, and it helps to be near the sea. “In warmer places, you’re going to be running into problems, because the ambient temperature is so much higher.”

Another element in the process is ash. “I’ve realised how important ash is to what I do. I’m getting a depth of flavour now that I never used to.”

All of this extraordinary knowledge is what makes Dave’s product as good as it is. It’s very good news for smoked salmon lovers everywhere that he’s aiming to increase production and satisfy demand from beyond Shetland’s shores.