Shetland lies on international trade routes, and with a coastline stretching for nearly 1,700 miles, it’s not surprising that many ships have met their end around the islands. Now, there’s a proposal that an outstanding example should enjoy permanent protection.

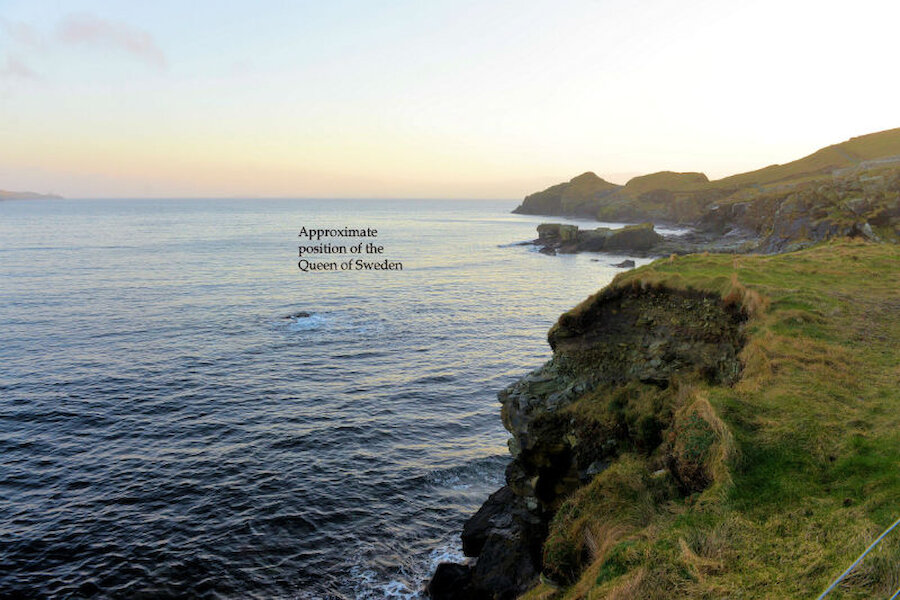

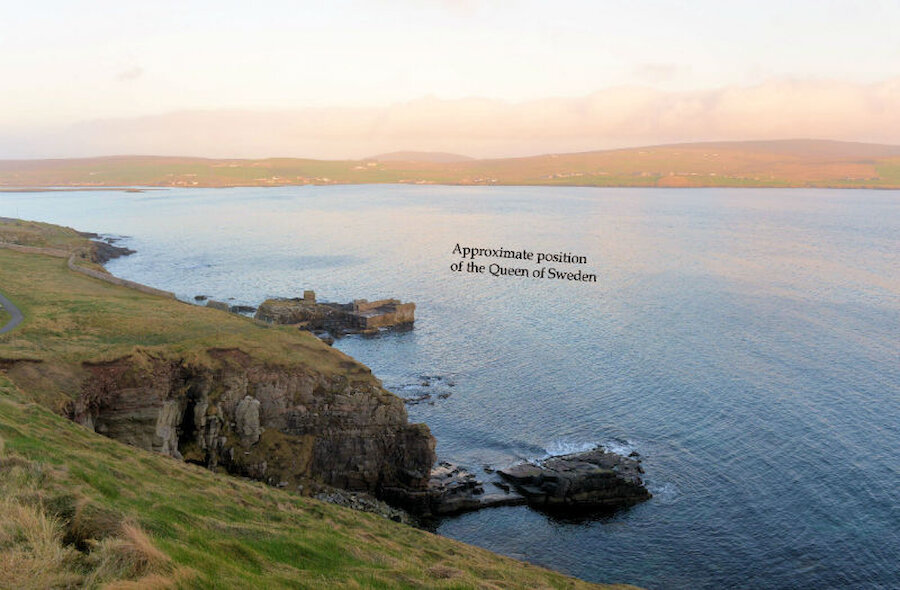

The vessel in question is the Drottningen af Swerige, or the Queen of Sweden, which hit a rock off the headland of the Knab, on the south side of Lerwick, on 12 January 1745. The ship’s master, Captain Carl Johan Treutiger, was seeking shelter from a storm in Bressay Sound, which forms Lerwick’s harbour.

The Queen of Sweden and another vessel owned by the same company, the Stockholm, had left Gothenburg three days earlier. Both vessels, partly loaded, were heading for Cadiz, where they were to pick up a cargo of silver and continue to China; and both came to grief on the east coast of Shetland. The Stockholm ran aground at Braefield, Dunrossness, on the same day. No lives were lost in either incident.