Without doubt, the Shetland dialect is one of the islands’ defining characteristics. In its essentials, it’s a form of Scots, but is noticeably influenced by Norn, the language brought by the Vikings that is still the basis of Faroese and Icelandic.

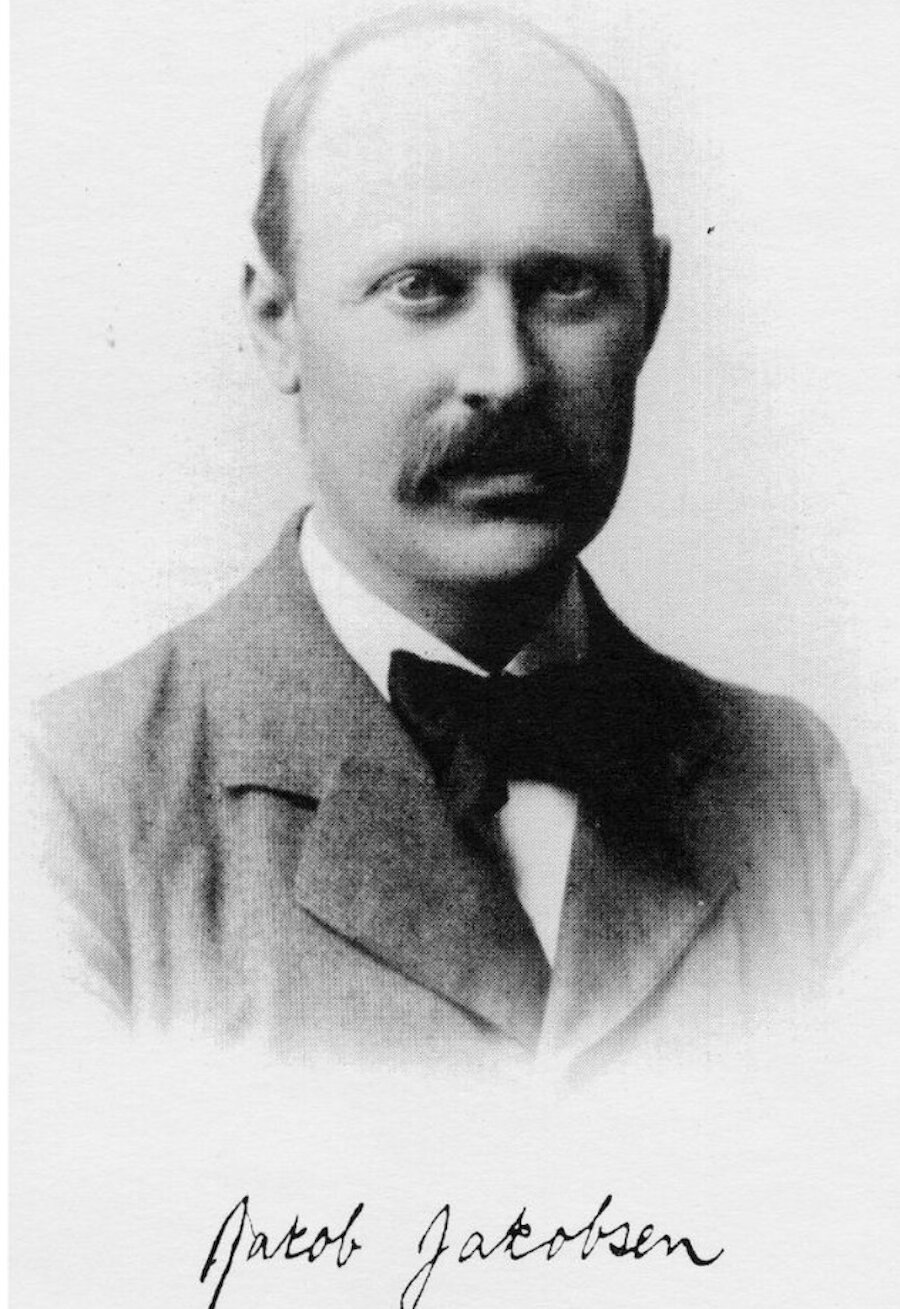

Many people have undertaken research into the dialect and its origins. In 1897, a Faroese scholar, Jakob Jakobsen, completed his doctoral thesis on the Norn language in Shetland, based on painstaking research. It remains the starting point for today’s linguistic researchers.

...the Shetland dialect is one of the islands’ defining characteristics...

One of these is Dr Viveka Velupillai, based at the University of Giessen in Germany. Her research interests include the study of contact linguistics, in other words the interactions between languages. She considers the effects on the structure and form of the languages involved. In a recent talk at the Shetland Museum and Archives, she introduced the large audience to a number of concepts that she uses in her work. For example, the interaction between two languages can be ‘balanced’ when, although each will absorb something from the other, neither is eliminated. On the other hand, the interaction can be ‘displacive’, with one language gradually being lost or diluted through attrition. In extreme cases, the ‘weaker’ language is abandoned as speakers shift to the dominant one.

In Shetland, Norn entirely replaced whatever language had been used by Pictish people prior to the Viking invasion. Later, Scots gradually displaced Norn but absorbed elements of it. For example, the Shetland words for birds or items connected with farming or boats are often recognisable to someone from Faroe or Iceland. An Oystercatcher is a Shalder in Shetland, a Tjaldur in Faroe, and the pronunciation is closer than the spelling. In a YouTube video that features Shetland poet Christine de Luca reflecting on language and dialect, she offers other examples; it’s well worth watching and listening.

...Shetland words...are often recognisable to someone from Faroe or Iceland...

More recently, standard English has made substantial inroads and Dr Velupillai gave many examples of how the Shetland dialect has been changing. Today, she suggested, the English ‘th’ sound seems to be supplanting the d and t sounds common in Shetland dialect. A question such as ‘does du mind [remember] da day?’ may nowadays be heard as ‘do you mind the day?). Forms such as ‘I am written’ are tending to change to ‘I have written’. We may also hear more people say ‘it’s raining’ rather than ‘he’s raining’ – something that seemingly occurs only in western Scandinavia, Shetland, Faroe and Iceland. Dr Velupillai feels that these changes are more audible in Lerwick and among younger people.

In order to try to understand how the dialect has been changing, Dr Velupillai has been analysing recordings of older Shetlanders held in the Shetland Archives. As members of the audience pointed out, in earlier generations the exclusion of Shetland dialect from schools was a major contributor to the decline. It did survive outside school; but as the mass media arrived in Shetland, Shetlanders were exposed to standard English in their homes. In particular, many would say that the introduction of television in 1964 accelerated the erosion of dialect thereafter.

From the mid-1970s, the arrival of many new inhabitants to support the growing oil industry also seems likely to have increased the pressure on the dialect; the islands’ population rose by around 30% in a decade.

...changes are more audible in Lerwick and among younger people...

In the face of these changes, interest in sustaining the dialect grew and a voluntary group, Shetland ForWirds, has made sustained efforts to encourage its use. Local media, including the quarterly magazine, The New Shetlander, and BBC Radio Shetland, have also been very supportive. The publication of a Shetland Dictionary and a guide to grammar and usage by the late John Graham was especially valuable. Many writers and poets, not all of them born in the islands, have written partly or exclusively in dialect and some books have been translated into it, including The Gruffalo. A new opera, Hirda, has been written in dialect and it’s due to be performed at the Celtic Connections festival in Glasgow on 8 February 2017.

...interest in sustaining the dialect grew...

So, what’s the future for the dialect? Dr Velopillai noted that the world is losing languages at a remarkable rate and the number of cases in which the process has been reversed is very small. One factor that may stabilise or increase use of the dialect is deliberate transmission from the older generation to the younger, with special emphasis on encouraging teenagers to use it; making it part of family life is important. By the same token, she added, it’s also best to avoid the dialect becoming associated purely with ceremonials, because it may then be regarded as quaint.

Dr Velupillai is at a relatively early stage in her research but her initial thinking was very well received by the audience and they will look forward to hearing more about her work in the years ahead. Meanwhile, it’s to be hoped that the initiatives already taken, and more in the years ahead, will keep the dialect relevant and alive for future generations.