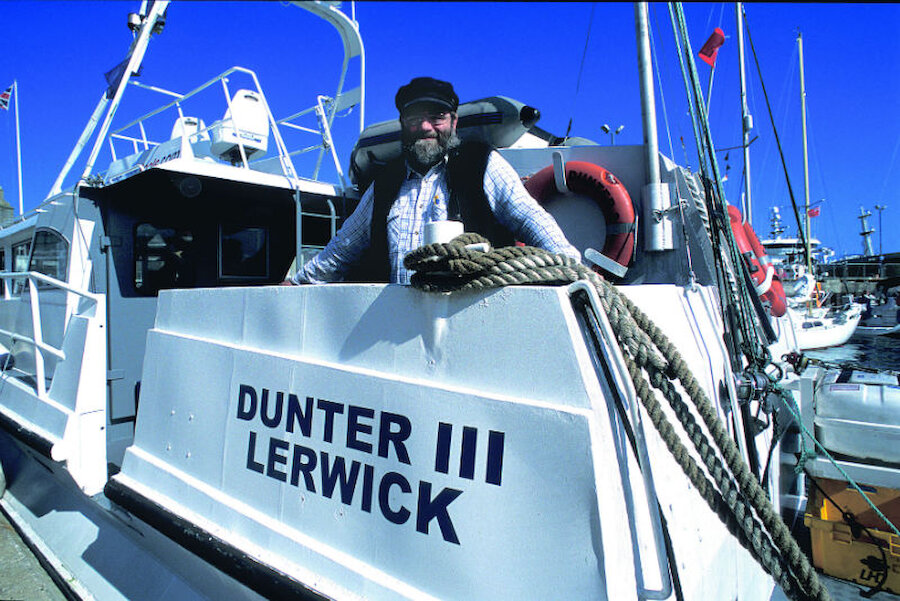

The Dunter III continues southwards, skirting the cliffs of Bressay and its coves and caves, some of which served as hideouts for smugglers or men trying to evade navy press-gangs. This coast is exposed to the worst that a North Sea storm can throw at it; one settlement, at Stobister, was allegedly abandoned “whan da olicks cam doon da lum” (that is, when ling fish came down the chimney). Much more recently, in 1997, the cargo ship Green Lily met her end here and a heroic coastguard helicopter winchman, Bill Deacon, was lost after rescuing the crew.

There is more fascinating detail as we round the Bard, the south end of Bressay, a tricky place for the unwary navigator. We pass another natural arch at the Giant’s Leg, and up on the clifftop is a huge gun that was installed during the First World War.

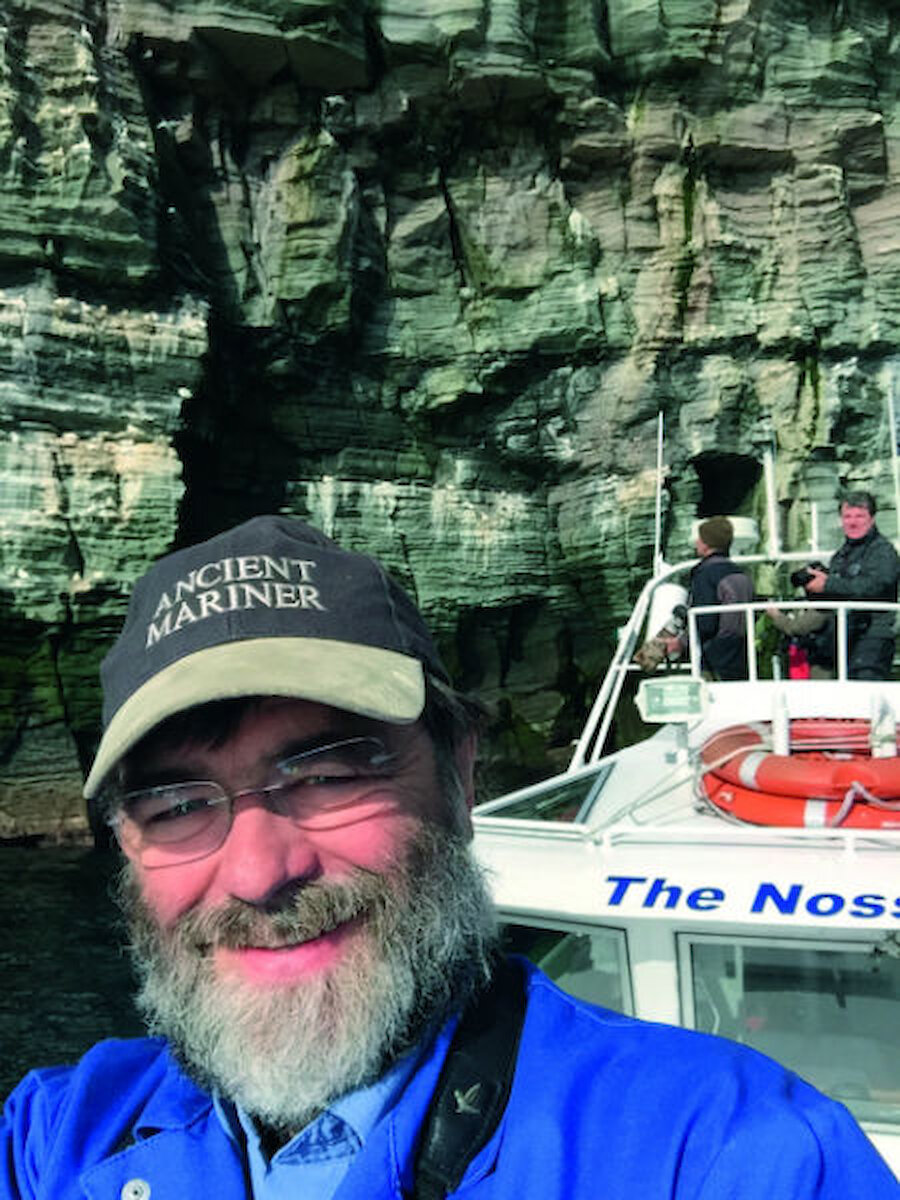

Onwards then, to the Orkneyman’s Cave, inside which it’s possible to moor Dunter III and explore using that underwater camera. Jonathan describes the cave and its natural history at some length, as well as telling the tale of how a Press Gang escapee, virtually dead from exposure, was apparently restored to life, though there were longer-term consequences. There’s an informative discussion here of the essential part that phytoplankton play in life on earth, producing more than half the world’s oxygen, and a strong warning about the insidious microplastics that enter the food chain every time we wash synthetic clothing materials.

The voyage back to Lerwick takes the boat past the Bressay lighthouse, with entertaining observations on the Stevensons who built it, the wrecks that lie hereabouts and a related example of fake news involving a Glaswegian cat and a kipper. Less entertaining, but very much to the point, are his thoughts on the threats to marine wildlife, be they from oil tankers or irresponsible fishing practices; at one point, Jonathan recalls, “a Danish power station was reported to be burning fish oil because it was cheaper than diesel.”