Climate and climate change are, quite literally, hot topics these days; news broke recently of a temperature record of 38°C in Siberia.

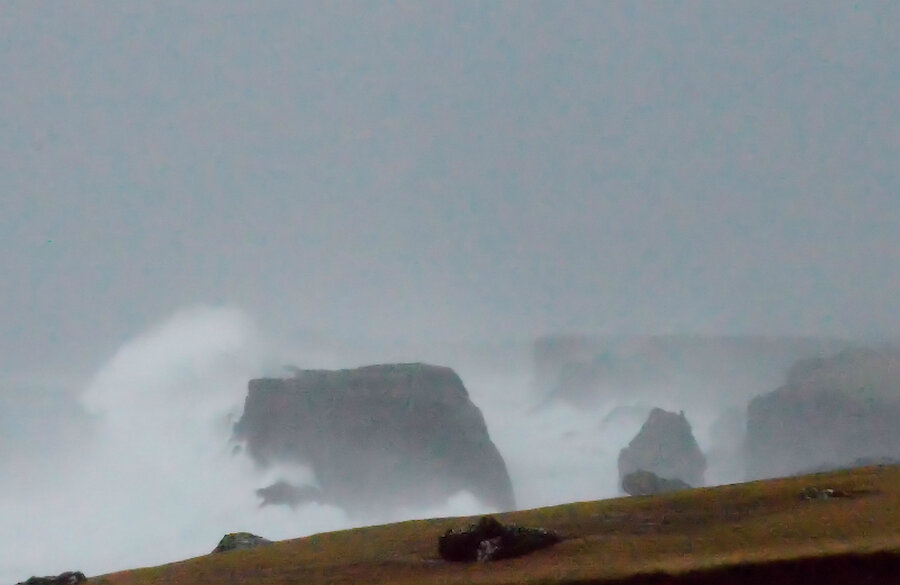

In the British Isles, conversations about the weather are something of a cliché and that’s perhaps even more true in Shetland. There’s no question: we do get a lot of weather, and the contrasts from day to day, or even hour to hour, can be dramatic, so there’s usually something to talk about.

It's not just us locals who think about the weather, of course. Visitors wonder what to pack: the sensible answer – as it usually is anywhere in the British Isles – is ‘everything’. Those who are thinking of making a permanent move to the islands may wonder how they’ll adjust to a quite different climate from the one they’re used to.