When I first made the trip from Shetland to Norway, it was in order to help stage an arts and crafts exhibition in Lerwick’s twin town, Måløy; and the strongest impression that remains with me was of the extraordinary warmth of the welcome that was accorded to our little Shetland group. Some of that warmth stems, of course, from the shared understanding that our islands were once part of the Norse realm; and our hosts spoke of Shetland as their ‘western isles’.

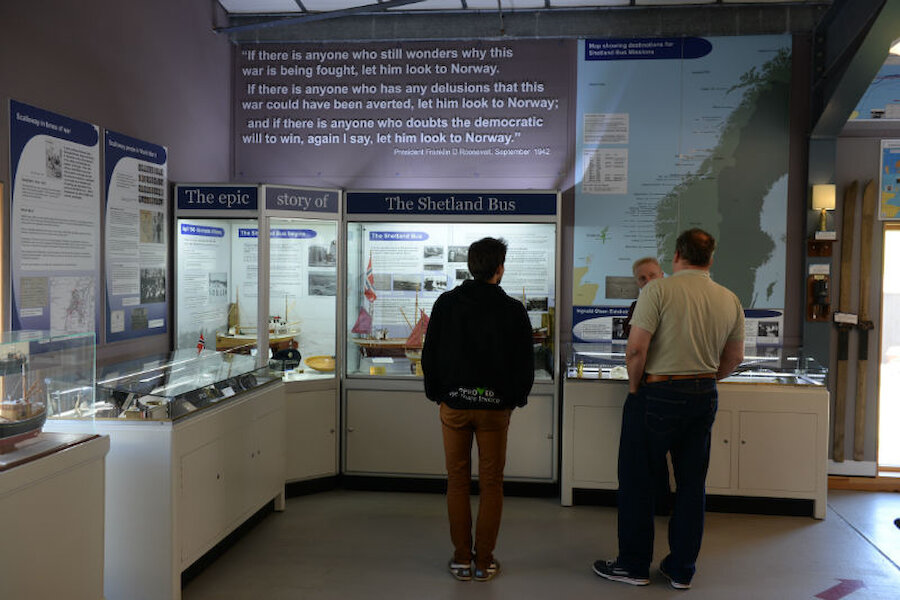

But there’s a much more recent reinforcement for those feelings. During the Second World War, Shetland offered a lifeline in the form of what became known as ‘the Shetland Bus’. The crews of small Norwegian fishing boats braved the North Sea during the darker winter months in order to support the resistance against a brutal Nazi occupation. They took in agents and supplies – weapons, ammunition, radios – and brought out refugees and resistance workers whose cover was in danger of being broken.