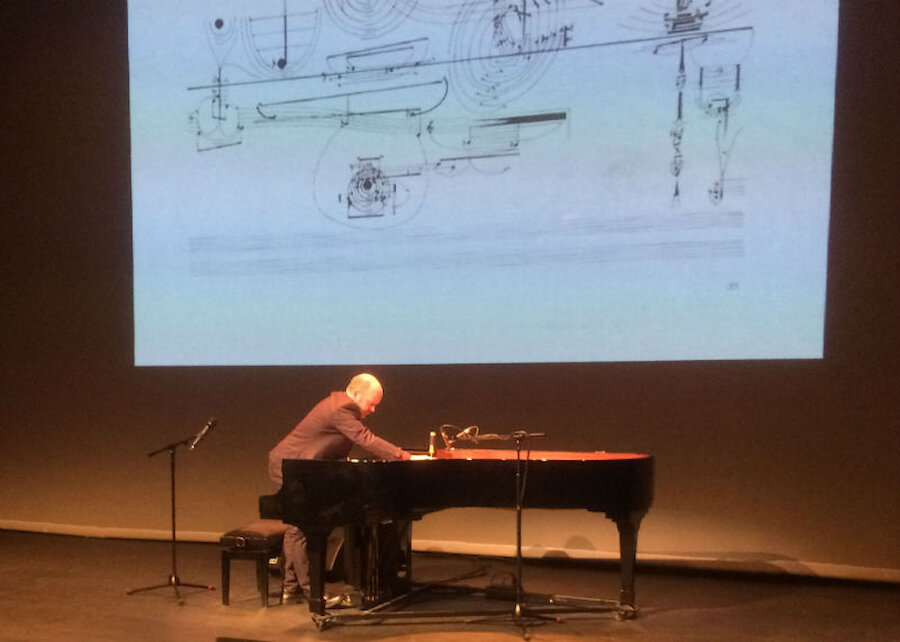

Neil Georgeson, originally from the village of Aith but now based in London, concluded his three-episode series of concerts with a sparkling performance that pushed every kind of boundary.

Neil has always been interested in the development of music; he’s artistic director of the Ossian Ensemble, a new-music group; and, whilst some of the musical items on the programme were familiar, others were (as he put it) a bit ‘out there’; one was a UK premiere.

In Shetland, where music really is at the heart of the community, the audience is used to unusual collaborations and novel sounds, whether home-grown, by performers such as Chris Stout, or during events such as the Shetland Folk Festival.

It helps, too, that Neil’s approach to his art is so utterly down to earth; and, whilst his art is beautifully-executed, Neil also comes across as musical scientist, testing ideas, hypotheses and techniques. Without fail, his sheer enjoyment and curiosity inspires the audience. If the television scientist, Brian Cox, made programmes about music, they’d probably feel a lot like Neil’s February concert in Mareel, Lerwick.