Shetland is known for many things - knitwear, ponies, bird rarities and fiddle music, for example – but the scale of the islands’ fishing industry isn’t always appreciated. That supermarket packet of haddock or cod will probably state its origin as ‘North-East Atlantic’, giving no clue as to where the fish was landed and who caught it.

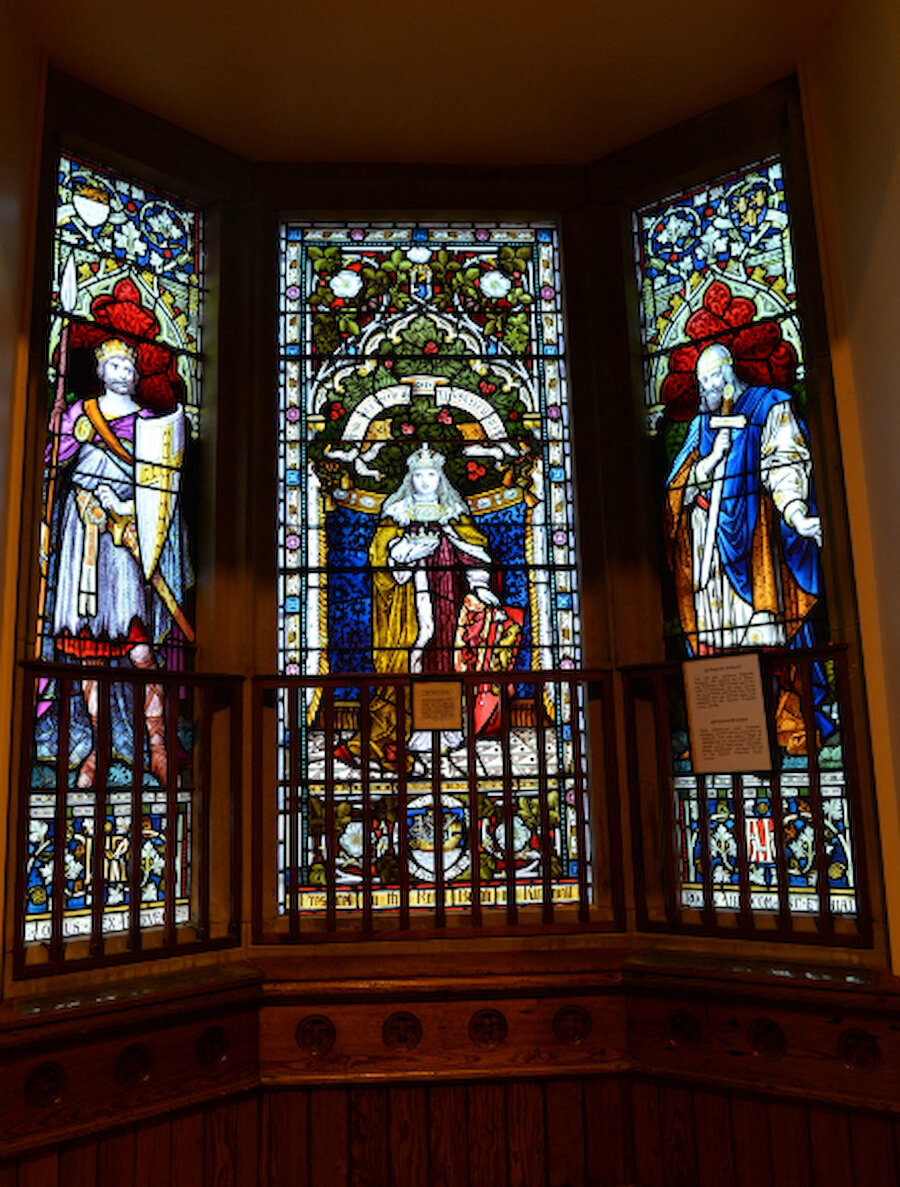

But it may well have been landed in Shetland, for fish is at the heart of our island economy. The islands’ fishing harbours – mainly Lerwick and Scalloway – land more fish than all the ports in England, Wales and Northern Ireland combined. In the late 19th century, the prosperity flowing from the ‘herring boom’ was reflected in the planning of a Victorian ‘new town’ to the west of Lerwick’s overcrowded ‘lanes’ area and in the confident and culturally sophisticated design of a new Town Hall that was fitted with some of the finest secular stained glass in Britain.