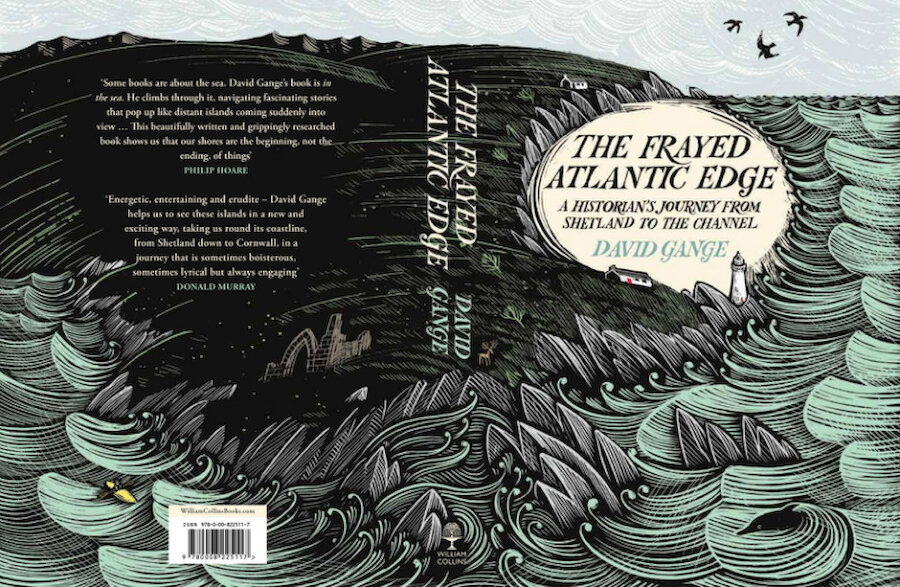

An absorbing new book recounts an extraordinary adventure by kayak that took historian David Gange all the way down the western coasts of the British Isles, beginning in Shetland.

The Frayed Atlantic Edge is based on the view that the significance of our coasts has been under-estimated and that one way of putting that right is to explore them by small boat. As his book demonstrates, doing so offers a perspective and a richness of experience that must once have been familiar to the earliest seafarers. In a very real sense, he asserts,

“the whole shape of British history is transformed by granting Atlantic coasts and islands a central rather than marginal role…All British history looks different when inland cities are made remote by seeing them from Atlantic shorelines, and the most powerful element of a year’s journey by kayak was immersion in that changed perspective.”