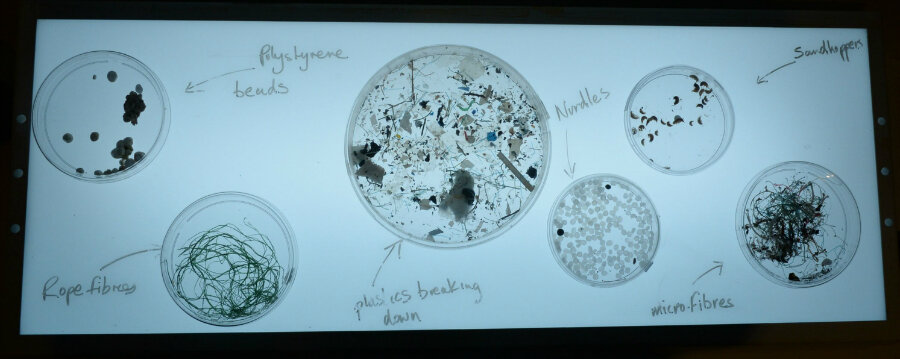

Plastic has been part of our lives for decades. It turns up in myriad forms, from food or drink containers to household equipment or major components of cars or boats. Unfortunately, too, it appears in many places where it does harm, for a large proportion of what we use is simply thrown away. Marine litter, most of which is plastic, has created huge, floating garbage patches; one of these, reportedly twice the size of Texas, lies off the Californian coast. There is increasing concern about the less obvious ways in which plastic is finding its way into the food chain. Micro-plastics, formed either through the erosion of larger pieces or the use of tiny plastic beads in products such as facial scrubs, are ingested by fish and ultimately by humans.

Over the years, people in Shetland have been instrumental in tackling the problem, both at a local level through the annual Voar Redd-Up (spring clean) and through supporting initiatives such as Fishing for Litter.